British Mercantile Trade Statistics, 1662–1809

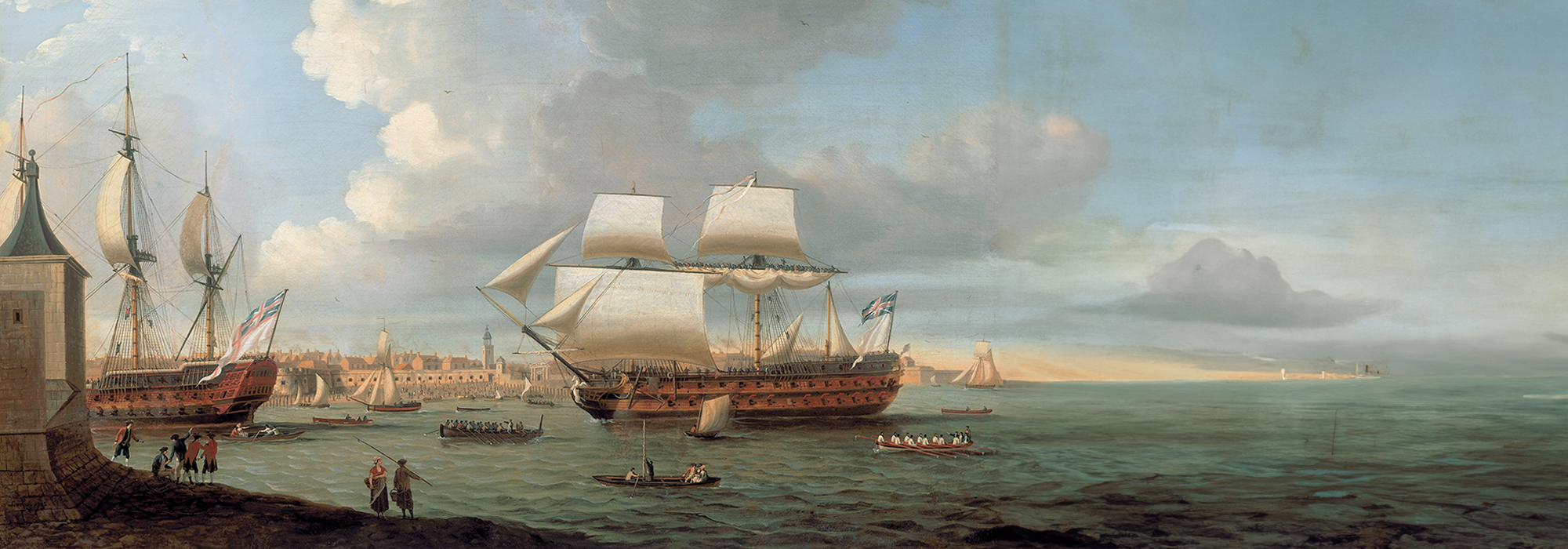

Track the movements of trade vessels and commodities over nearly 150 years

This collection offers a unique and fascinating window into the development of British commerce during the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. Global in its scope, it offers vital materials for historians of trade, empire, and those interested in the reach of the British state.Senior Lecturer in Naval and Maritime History, University of Exeter

Access the full collection

Access the full archive of British Mercantile Trade Statistics, 1662–1809.

Institutional Free Trial

Start your free trialRegister for a free 30-day trial of British Mercantile Trade Statistics, 1662–1809, for your institution.

Institutional Sales

Visit Sales PagesellFor more information on institutional access, visit our sales page.

Already have a license? Sign in.

Explore the intricacies of British maritime trade during the "long eighteenth century".

Containing over 47,000 images drawn from files at The National Archives (UK), British Mercantile Trade Statistics, 1662–1809 charts nearly 150 years of British trade and shipping in remarkable detail. Throughout this period, Britain’s increasing naval capabilities and the expansion of lucrative maritime trade networks fuelled significant economic growth. Frequently built upon exploitation and enslaved labour, the establishment of British trading outposts and plantations throughout Africa, Asia, the Americas, and the Caribbean laid the foundations for a worldwide empire and secured access to sought after commodities, such as sugar, tobacco, and textiles. This comprehensive collection includes trade ledgers, registers, and indexes that supply detailed statistical data on trade throughout the “long eighteenth century”, a pivotal era in the development of British and global commerce.

A key theme can be identified within this period: a growing determination on the part of British governments to record, regulate, and promote maritime trade. The Board of Customs was established in 1671. In 1696, William Culliford was appointed the first Inspector-General of Imports and Exports. The official records in this collection catalogue the receipt and shipment of goods at ports across England, Scotland, and Wales. The sources likewise document Britain’s balances of trade with other countries and provide information on numerous vessels and their voyages.

This collection also boasts the official registers of “Mediterranean passes”. From 1662 until the early 1820s, these were issued to British ships by the Lord High Admiral. A form of diplomatic passport, supported by a complex treaty system, passes granted immunity from Barbary privateers patrolling the waters of the Mediterranean, as well as those around North Africa, North America, and throughout the West Indies. The pass system thus helped to facilitate Britain’s rise to a commercial and maritime power. None of the passes have survived. Thankfully, the registers detail which vessels were issued passes, their port of embarkation and destinations, as well as additional information on their size, crew, and defences.

British Mercantile Trade Statistics, 1662–1809 will appeal to those investigating the colonial, economic, and maritime dimensions of British history throughout this period. It should also interest those exploring broader themes, such as the escalation of global trade and the development of the fiscal-military state. A rich and versatile resource, it forms a natural evidential counterpart to many of BOA’s collections relating to the theme of “Colonialism and Empire”.

Contents

British Mercantile Trade Statistics, 1662–1809...

Track the movements of trade vessels and commodities over nearly 150 years

Discover

Highlights

Licensed to access Rules of the Mediterranean Passes

This document reveals how, in May 1682, Orders in Council established seven rules for granting “Mediterranean passes”. Passes were only issued by the Lord High Admiral to English (later British) or colonial-built vessels. Ship masters had to be English or Protestant denizens and two-thirds of the crew had to be English subjects. A surveyor's certificate and an oath confirming the ship's construction and the crew's nationality were also required. Fines were imposed if passes were not returned.

Licensed to access The East India Company and the Spice Trade

By the mid-1700s, the East India Company had amassed vast wealth, and was backed by a formidable private army. Established in 1600 to compete with the Portuguese and Dutch in the spice trade, the company sourced cardamom, cinnamon, cloves, nutmeg, turmeric, and pepper from across the Indian subcontinent and Southeast Asia. These commodities were exported to Britain and became essential for cooking, medicine, and preserving. Lucrative and undoubtedly exploitative, the spice trade formed a significant component of Britain’s economic development.

Licensed to access American Colonies and Tobacco

Throughout the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, tobacco was the most valuable commodity imported into Britain from its American colonies. The trade ledgers shed light on the quantity of tobacco that was exported from major tobacco plantations throughout Virginia and Maryland. Relying heavily on enslaved African labour, the cultivation of this cash crop formed the economic foundation of several colonies and consequently fuelled the expansion of slavery in America.

Licensed to access Shipping Records and the 1786 Registration Act

Following the 1786 Registration Act, Britain’s shipping accounts became more comprehensive. The ledger for 1790 is prefaced by a letter (images 1 to 5) from the Inspector-General, Thomas Irving, to the Prime Minister, William Pitt. Irving explained how he had worked to “extend and Improve the system of keeping the Accounts”, hopefully rendering them of “much more utility to Government”. He likewise outlined how the accounts were divided into three sections: “Navigation”, “Revenue”, and “Commercial”.

Insights

The archival documentation in this collection can nourish diverse lines of research. For example, it provides invaluable insights into the commercial policies and strategies pursued by the emerging British state during a period of sustained economic growth. The sources likewise furnish us with a comprehensive overview of the nature and development of Britain’s trade routes and relationships. Crucially, they also illustrate how Britain’s commercial interests, networks, and strategies laid the foundations for a vast, global empire.

The collection contains detailed information on a multitude of trade vessels, such as their names, crew sizes, ownership, defensive capabilities, tonnage, and the nature of their construction. This data gives us a vivid sense of the developing maritime infrastructure that facilitated British trade during two centuries of economic expansion.

English (and subsequently British) governments utilised diplomacy in order to reduce threats to merchant shipping. Following a peace treaty with Algiers in April 1662, “Mediterranean passes” were issued to native ships by the Lord High Admiral. These documents ensured protection from corsairs and privateers hailing from the Ottoman-controlled territories along the Babary Coast of North Africa.

Despite the name, “Mediterranean passes” were issued to vessels traversing a variety of trade routes—out of 3,430 passes issued from 1771–1773, only 505 were given to vessels bound for the Mediterranean. 440 were given to ships bound for Africa, 665 were issued to vessels heading for the Caribbean, 942 were for ships sailing to North America, and 143 for boats sailing for the Wine Islands (most notably Madeira).

Throughout the seventeenth century, the registers of “Mediterranean passes” were somewhat limited in terms of the information that they contained. As trade networks became more extensive and lucrative, the state required more precise data regarding, and regulation of, maritime trade. During the early 1680s, efforts to regulate and authenticate vessels increased. The registers began to include docking locations and return dates. By 1730, intended destinations were being recorded.

The statistics in this collection were compiled by the Inspector-General of Imports and Exports, a position established by the Board of Customs in 1696 and originally occupied by William Culliford, a former revenue commissioner. In 1703, he was succeeded by the politician and former Commissioner of the Excise, Charles Davenant, who held this position until his death in November 1714. The economist, Henry Martin, was then appointed, serving until his death in 1721. Martin was the last Inspector-General to fulfil his duties until the office of Inspector-General of Imports and Exports was refurbished. In 1786, Thomas Irving was appointed.

The trade ledgers in this collection detail key imports and exports. For example, "Cocoa nutts” and tortoise shell were shipped to Britain from Barbados; tobacco and "Indico" from Bermuda; raccoon skins and pimento from Carolina; and a good deal of linen, oysters, and salmon arrived from neighbouring Ireland. Meanwhile, Britain exported beef, butter, and vinegar to Africa; books, candles, and flax to the Canaries; whilst “Pistolls” and swords made their way to East India.

Unlock Historical Research for Your Institution

Provide your students and researchers with direct access to unique primary sources.

Related Media

British Mercantile Trade and the Royal Navy During the Long Eighteenth Century Contextual Essays