British Colonial Rule in the Cape of Good Hope and Basutoland, 1854–1910

Administrative and economic change during a transformative era in South African history

Throughout the nineteenth century, the Cape was probably the most important, the most populous and the wealthiest British colony in Africa.Emeritus Professor, SOAS University of London

Access the full collection

Access the full archive of British Colonial Rule in the Cape of Good Hope and Basutoland, 1854–1910.

Institutional Free Trial

Start your free trialRegister for a free 30-day trial of British Colonial Rule in the Cape of Good Hope and Basutoland, 1854–1910, for your institution.

Institutional Sales

Visit Sales PagesellFor more information on institutional access, visit our sales page.

Already have a license? Sign in.

Explore the intricacies of British colonial rule in the Cape colony during the later nineteenth century

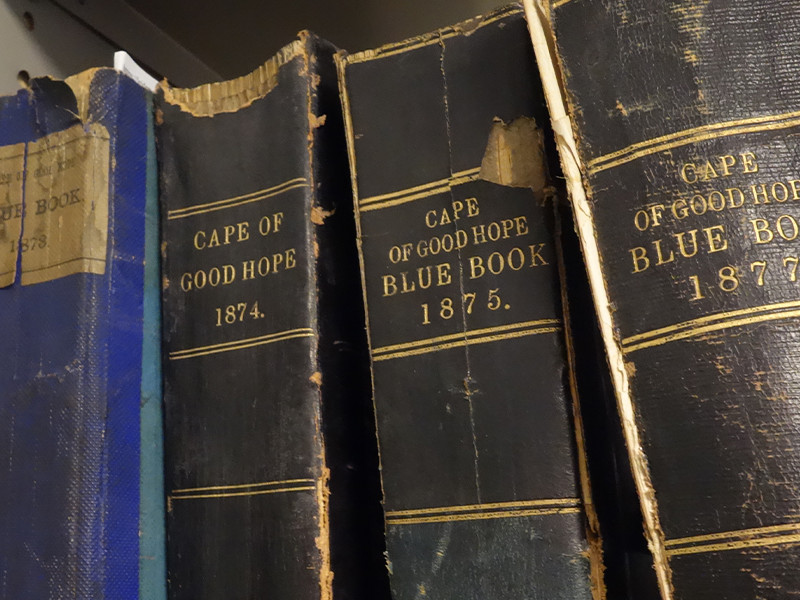

Containing over 140,000 images, British Colonial Rule in the Cape of Good Hope and Basutoland, 1854–1910, charts over 50 years of British colonial rule in southern Africa. Settled by the Dutch East India Company in 1652, the colony came under British control in 1806. In 1910, it became a province of the newly formed Union of South Africa. Britain granted the colony the right to elect a legislature in 1853. In 1872, full internal self-government was established. During the nineteenth century, it emerged as a commercial hub—the discovery of diamonds and gold in the 1860s rendered it the most important and prosperous British colony in Africa. This collection tracks the administration of the Cape from 1854 to the formation of the Union of South Africa.

It also includes material on British Kaffraria—the southern region between the Keiskamma and Yei rivers—and Basutoland (present-day Lesotho), a British Crown colony that was bordered by the Cape, Natal, and Orange River colonies. Kaffraria came under Cape control in 1865. In 1871, so did Basutoland. The documentation relating to this territory includes annual and legislative reports, proclamations, correspondence with local rulers, and reports on rebellions.

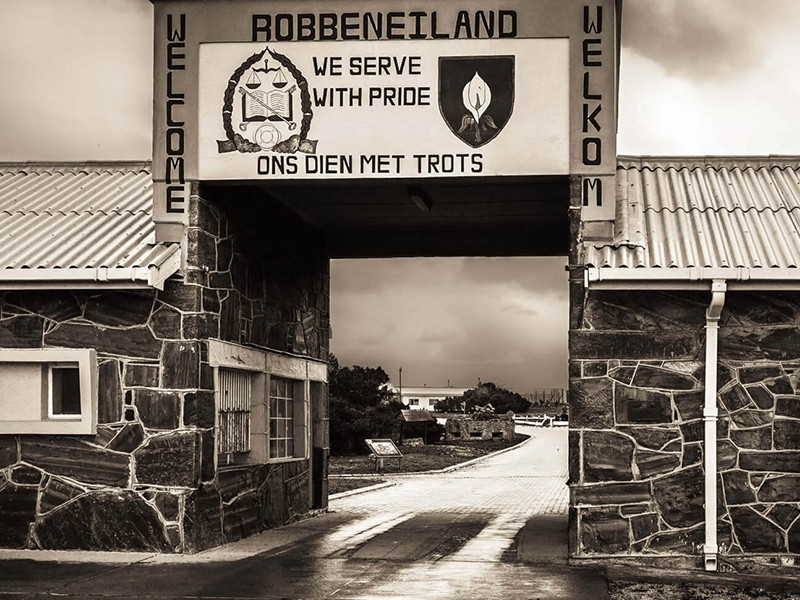

This collection evidences significant historical trends, such as the development of constitutional governance and infrastructure in the region, as well as the growth of key industries, such as mining and the production of cotton, ostrich feathers, and wine. You will come across records regarding the use of Robben Island, reports relating to the development of the colony’s education system, as well as information on the construction of roads and railways, and on the failed Jameson Raid of 1895. Although the Cape colony was controlled by a minority class of white settlers, the sources nevertheless provide valuable glimpses into African cultures and societies, including examples of resistance to colonialism.

British Colonial Rule in the Cape of Good Hope and Basutoland, 1854–1910, will be of interest to students, researchers, and lecturers investigating and delivering courses on the social, political, and economic development of South Africa. It should also appeal to those exploring the broader histories of Africa and colonialism. A comprehensive and versatile resource, it forms a natural counterpart to many of our primary source collections that we have grouped under the theme of “Colonialism and Empire”, such as British Mercantile Trade Statistics, 1662–1809, and Apartheid Through the Eyes of South African Political Parties, 1948–1994.

Contents

British Colonial Rule in the Cape of Good Hope and Basutoland, 1854–1910...

Administrative and economic change during a transformative era in South African history

Discover

Highlights

Licensed to access Basutoland Annexation Bill, 1871

This transcript (pp. 7–12) is from a meeting of the Cape colony’s Committee on the Basutoland Annexation Bill (7 July 1871). J. H. Bowker, Commandant of the Armed and Mounted Police in Basutoland, argued for annexation due to the region being surrounded by rival territories. It “would pay itself”, he claimed, through increased agriculture and trade. Bowker noted that many Basutos had adopted “civilised habits” due to the influence of Christian missionaries and would therefore integrate easily. This optimism proved naïve.

Licensed to access Report of the Keeper of the Archives for the Year 1896

This report, written by the Cape colony’s Keeper of the Archives, Hendrik Carel Vos Leibbrandt, outlines efforts to preserve its records. He details the retrieval and archiving of court records, treaties, contracts, and administrative papers dating from the periods of British and Dutch rule, despite challenges, such as damaged documents and beetle infestations in book bindings. The report underscores Britain’s intent to document its control over the colony, ensuring legal defensibility and preserving its administrative legacy.

Licensed to access Illicit Diamond Trade, 1862

In 1867, a Boer farmer’s son discovered diamonds near the Orange River, transforming the Kimberley region into a hub of British wealth and exploitation. This document addresses illicit diamond dealing, including a draft bill from 1862 that made licences mandatory for brokers, cutters, dealers, and exporters in Griqualand West. Detailed documentation of transactions was also required, including values, weights, and the identity of buyers, with penalties such as fines of up to £1,000, imprisonment, confiscation of diamonds, or license suspension for violations.

Licensed to access Examination Papers for the Public Service Certificate, 1861

Those wishing to enter the Cape colony’s civil service were vetted via examination. As this exam paper illustrates, candidates wishing to gain the Public Service Certificate had to be familiar with British history, especially with the “Rise and Progression of the English Constitution”. They also had to be capable of translating Latin, Dutch, German, and French into English (and vice versa), and have a grasp of arithmetic, algebra, plane geometry, and physical geography.

Insights

This collection surveys British rule in the Cape of Good Hope from 1854 to 1910. British rule in the region began in 1795, when the colony passed briefly into their hands. Established by the Dutch East India Company in 1652, it developed into a settler community, attracting Dutch, German, and French Huguenots, who came to be known as Afrikaners or Boers. Escalating tensions between settlers and the indigenous Khoisan population resulted in the Khoikhoi–Dutch Wars (1659–1660 and 1673–1677). Dutch financial decline left the Cape vulnerable. In 1795, during the French Revolutionary Wars, British forces occupied it, valuing its strategic location from which they could control trade routes to India. This alarmed Afrikaners, who feared interference in their way of life. In 1803, the Treaty of Amiens returned the colony to the Dutch. It was re-occupied by Britain in 1806 and secured via the Treaty of Vienna in 1814.

The British government granted the Cape colony self-government in 1853. Its expansion followed the familiar pattern whereby the British annexed neighbouring territories and transferred them to Cape control—Basutoland was annexed in 1868 and handed to the Cape parliament in 1871. This process, and the resistance that it generated, can be surveyed in this collection. For example, the Basotho people resisted attempts to disarm them so vigorously that in 1884 the Cape parliament opted to transfer control of Basutoland back to Britain.

This collection tracks the growth of the Cape’s infrastructure in remarkable detail. Government reports detail the development of state institutions, such as schools, prisons, hospitals, museums, and even the colony’s archives. Accompanying reports, such as those compiled by the Department of the Chief Inspector of the Board of Public Works, document irrigation and forestry projects, trigonometrical surveys, as well as the construction of bridges, harbours, lighthouses, roads, and railways. There are even reports considering the width of roads and accounts showing spending on safes for post offices, as well as the planting of trees around state buildings.

The Cape, with its diverse population, was the most populous British colony in Africa during the nineteenth century. This collection illuminates its shifting demography. Internal migration patterns can be tracked and reports from the colony’s Immigration Board evidence the Cape’s position within imperial immigration networks. Demographic information can also be found in the annual registers of births and deaths. Reports compiled by the administrators and inspectors of schools, hospitals, and prisons likewise detail people’s ethnicity, religious beliefs, literacy levels, and general health.

The collection features reports on the use and management of Robben Island. The Dutch confined political prisoners there, as did the British—the island was used for this purpose until the abolition of Apartheid in 1996. By the 1850s, it was also a leper colony. Those with the disease were forcibly confined to the island and suffered from neglect and inhumane conditions. It likewise served as a quarantine station during outbreaks of diseases, such as smallpox. A “lunatic asylum” was later established. The uses of the island during the nineteenth century cast light on disturbing dimensions of Victorian colonial outlook regarding the mentally and physically ill, as well as those opposed to Britain’s imperial project.

Sources, such as the Blue Books on Native Affairs, evidence the self-confident colonial mindset, illustrating how Cape administrators embraced the lofty, liberal concepts of civilisation, progress, and modernity, as well as Protestantism. Yet this collection also grants insights into African cultures and communities, albeit through the prism of the white settler gaze. Sources reveal how indigenous people responded to, and frequently resisted, the encroachment and exploitation of the colonial administration.

Unlock Historical Research for Your Institution

Provide your students and researchers with direct access to unique primary sources.

Related Media

.svg)