The Bystander, 1903–1940

"The Bystander shall not be glanced through and then thrown away, but read as well." The Bystander, 9 December 1903.

Such is the depth of this rich and eclectic resource that it is difficult to think of a topic - political, social, cultural, economic, diplomatic, military, environmental - for which there will not be relevant - and probably unexpected - material.Historian

Access the full collection

Access the full archive of The Bystander, 1903–1940.

Institutional Free Trial

Start your free trialRegister for a free 30-day trial of The Bystander, 1903–1940, for your institution.

Institutional Sales

Visit Sales PagesellFor more information on institutional access, visit our sales page.

Already have a license? Sign in.

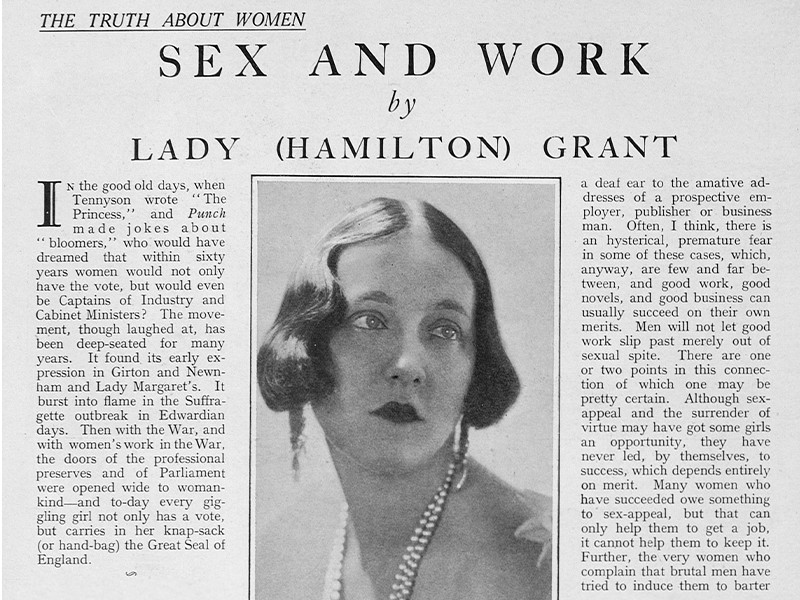

Discover the attitudes, interests, and leisure activities of Britain’s social elite at a time of profound cultural and social change.

Established in 1903 by George Holt Thomas (the son of illustrator and social reformer William Luson Thomas, founder of The Graphic), The Bystander ultimately joined a series of publications belonging to The Illustrated London News (ILN). In 1940 The Bystander merged with its sister title: The Tatler. It thus became known as The Tatler and Bystander. Much like its successor, The Bystander focused on British “high society”, thereby appealing to a conservative, affluent readership. Publishing articles on fashion, theatre, and sports, this publication reflected everyday life amongst Britain’s social elite, its coverage typically defined by a suitably whimsical, satirical tone. This collection includes over 136,000 images collated from nearly 2,000 issues of The Bystander, published between December 1903 and October 1940.

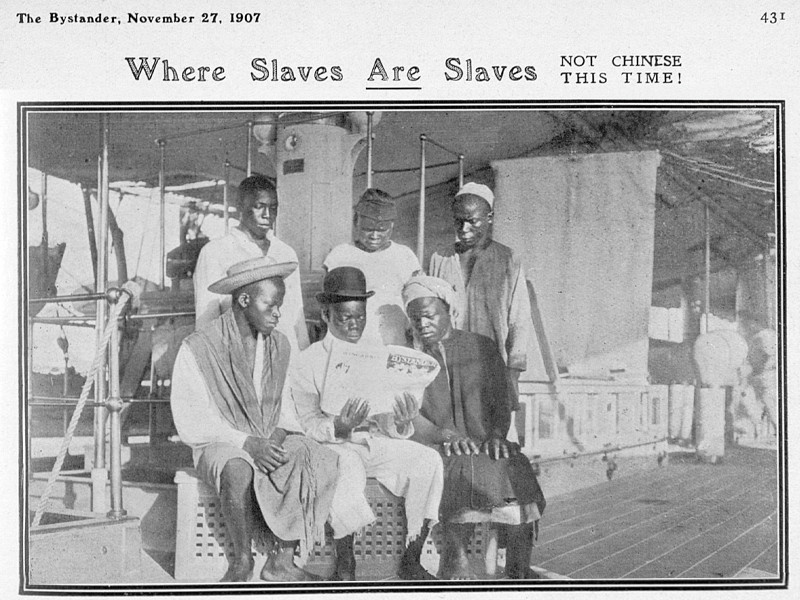

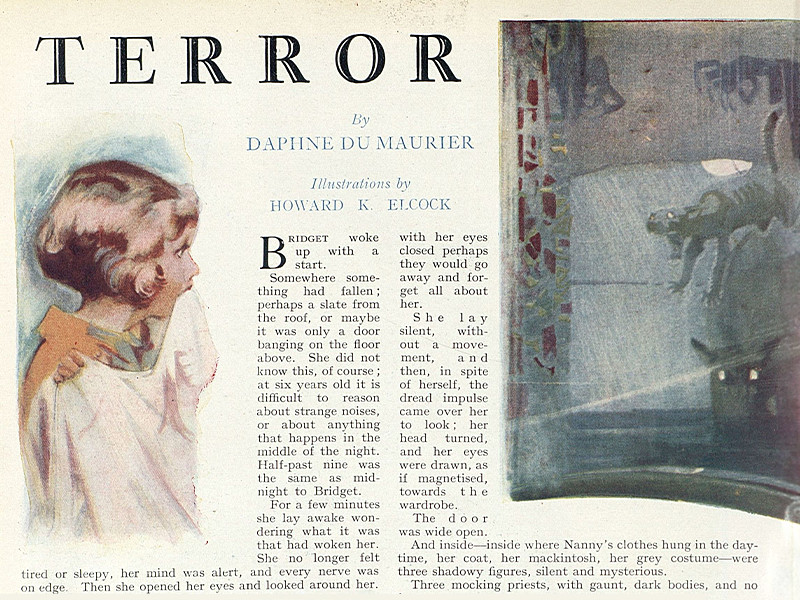

The Bystander supplied light-hearted reading. Within its pages one could find the latest gossip on the aristocracy, advice on antiques, and reports on the fishing and hunting seasons. Yet it also provided a platform for some of the most influential writers and artists of the day. It published short stories by celebrated authors such as Daphne du Maurier and Hector Hugh Munro — better known by his pseudonym “Saki” — as well as contributions from cartoonist and humourist Bruce Bairnsfather (most notably his popular “Old Bill” cartoons about the First World War). The Bystander yields exciting material for those working in the fields of literary studies, the history of art, and social history. Much like other titles contained within British Illustrated Periodicals, 1869–1970, The Bystander reflected the racism and discrimination that pervaded British society during the heyday of the Empire. It is a rich resource for students and researchers wishing to explore the themes of colonialism, ethnicity, and race within modern history.

Contents

The Bystander, 1903–1940...

"The Bystander shall not be glanced through and then thrown away, but read as well." The Bystander, 9 December 1903.

Discover

Highlights

Licensed to access "Jews and Judeophobes"

3 December 1913:

Commenting on the political situation in pre-war Germany, this article (image 30) denounces antisemitism as a quintessentially “German” problem whilst, ironically, reinforcing the legitimacy of antisemitic stereotypes amongst a British audience.

Insights

Whilst The Bystander kept its readership abreast of current affairs in regular columns such as ‘The Bystander’s Notes’, it often prioritised light-hearted content, aiming simply to entertain. For instance, instead of discussing foreign affairs the paper’s “From Abroad” section contained travel advice and reviews of popular holiday resorts.

Though it maintained a jovial, satirical tone, The Bystander remained supportive of the British establishment and its imperial ethos. It perpetuated racist and xenophobic stereotypes and even made light of the institution of slavery.

The Bystander printed many of Captain Charles Bruce Bairnsfather’s popular “Old Bill” cartoons. These drew upon Bairnsfather’s military experiences in France during the First World War. In a collected edition of Bairnsfather’s cartoons, published in 1918 under the title The Bystander’s Fragments from France, the paper’s editor reflected upon the appeal of “Old Bill” and his pals “Alf” and “Bert”. They captured “the spirit of the simple man caught in the vortex of a war of unaccustomed complexity”, he observed, providing “proof that human nature and humour survive in the heart of horrors”. Today, Bairnsfather’s work for the The Bystander grants important insights into the British imagination and outlook during the Great War.

As with its sister titles, The Bystander featured contributions from those at the forefront of British art and literature. It was the first publication to print stories by Daphne Du Maurier, one of the most popular British novelists of the twentieth century. In fact, Du Maurier’s uncle, William Comyns Beaumont, edited The Bystander.

The Bystander reveals the evolving diet of its readership. Its regular “Menu” column suggested recipes and supplied culinary inspiration for those hosting dinner-parties. Its “London Nights” column likewise casts light upon the development of restaurant culture within the city. As the historian Phil Lyon (2020) has observed, dining out became increasingly prevalent in the decades after the First World War. Although “a night out” at a London restaurant had — naturally — long been popular amongst wealthy citizens, by the 1930s, as Lyon has highlighted, “conditions were now right for the pleasures of dining out to be extended more regularly to other sections of society”.

Unlock Historical Research for Your Institution

Provide your students and researchers with direct access to unique primary sources.

Related Media

Guide to British Illustrated Periodicals, 1869–1970 Contextual Essays

.svg)