The Tatler has, since its original form in the early eighteenth century, been a publication concerned with status and social ideals. The original Tatler was very much focused on guiding the emerging middling sort on how to behave in a variety of public and private situations, and this ‘guide to life’ model can also be seen in the twentieth-century revival of the publication. Relaunched by literary critic and journalist Clement Shorter in 1901, the early adverts promised ‘the lightest, brightest and most interesting Society and Dramatic Paper’.[1] Published weekly on Wednesdays, it originally retailed at 6d a copy, but by 1918 it cost one shilling, reflecting its elite appeal. However, it was not only interested in reporting on the life of the country set in their rural setting; the urban life of the ‘global celebrities’ (Clement Shorter’s term) was a significant feature, too.[2] In the first sixty years of its revival, the focus was on society, culture, leisure, and fashion. It regularly featured on its front pages and in its famous photographic spreads a combination of ‘old money’ and new faces, with a mix of entertainers and earls, politicians and princesses, and tennis players alongside the titled. As The Tatler covered the lives and interests of the elites for a primarily (but not exclusively) elite audience, it is a great resource for scholars of the class and gender ideals of the age, even if some of those who were featured in the magazine were there because they had transgressed these standards.

One of the main features of The Tatler was its coverage of the Season. This elite institution, with origins in the sixteenth century, saw considerable change during the twentieth century. A loosely used term to describe the elite practice of attending cultural events, parties, and the Royal Court during spring and early summer, it was connected to both political and social life.[3] For those young women who were making their debut at Court, there was a wider social whirl of afternoon teas, cocktail parties, and formal balls, where they could be established as full members of elite society. These were all closely reported in the magazine and the families of debutantes sought out complimentary coverage within The Tatler, ideally with photographs from their parties, or one of their debutante portraits. Increasingly, the Season became broader to include sporting championships, nightclubs, and newly launched events such as the Glyndebourne Opera Festival.[4] The faces included changed too, with artists, athletes, and Americans included in the coverage; in 1963 the cover girl for the ‘London Season’ edition was not an aristocrat, but the model Jean Shrimpton.[5] More critically, the practice of the debut presentation at Court ended in 1958, leading to extensive coverage in The Tatler for this final year.[6] However, despite these changes, the Season remained key content, and the idea of elites at play was one of the main features of the magazine.

This was because play was important work for the elite. Traditionally, aristocrats were the ‘leisured’ class, and their ability to remain visibly leisured was part of how they remained distinct from the professional and middle classes. This was reflected in the coverage of social elites in The Tatler. For example, hunting and shooting featured regularly in the magazine from its earliest edition through to the mid-1960s; these were expensive activities which not only demonstrated participants’ skills, but being able to use one’s own land for sport meant that the status gained through the stewardship of an estate was asserted and amplified.[7] However, as the readership was increasingly drawn from those outside of the landed elite, there was some recognition that these practices belonged to a distinct social world.[8] Therefore, more fashionable activities were also featured, such as tennis, motorsport, and skiing. It was not just about the competitions; reports on the Wimbledon tennis championship not only covered accounts of sporting prowess, but also the associated parties and celebrity gossip, showing how ‘Society’ was as important as sport.[9] There were also regular reports about traditional holiday hotspots and new destinations, such as the Mediterranean and the Caribbean Islands.[10] The social change was also reflected in the nature of the reports; features on the lifestyles enjoyed by those who had travelled to the south of France in the 1920s contained oblique references to a more ‘open’ lifestyle enjoyed by the young and beautiful.[11] Although they usually seem frivolous, the reports of elites at play reflected the socio-economic and cultural change of the period.

These changes can also be seen in The Tatler’s fashion columns. In the early part of the twentieth century, there was a great deal of emphasis on providing guidance for debutantes, especially in the ‘My Lady’s Mirror’ column. However, increasingly advice was given to readers who were engaging in a wider set of activities. Clothing advice was given to those taking up fashionable sports such as skiing and driving, reflecting the ongoing ‘guide to life’ ethos of the publication.[12] During the First World War much of the fashion reporting was focused on how it was patriotic to continue to spend on luxuries in order to support the clothing industries in France and Britain, and advertisements encouraged women to look good for the soldiers on leave as a way of improving national morale.[13] Therefore, it is not a surprise that two days after the Armistice was signed, the ‘Highway to Fashion’ column celebrated the fact that women could swap their monotonous uniforms for attractive dresses to harmonise ‘with the spirit of happier times’.[14] Similarly, although there was significant pragmatism in the fashion reporting during the Second World War, this soon returned to a strong emphasis on glamour during the 1950s.[15] The fashion pages were also driving change. Photographs were central to the creation and continuation of the new celebrity status of the fashionable ‘Bright Young Things’, which in turn attracted new readers, especially during the interwar period.[16] This meant that it became attractive to advertisers, and in the 1920s, it was one of the British magazines with the highest proportion of adverts.[17] The different types of products advertised (which included cars, sports equipment, beauty treatments, holidays, and clothing) reflected the presumed taste or aspirations of its readers. However, although many of these advertisements had an ‘exclusively feminine appeal’, there was a significant male readership of The Tatler, too.[18] Many of the fashion and consumer features were appealing to both male and female consumers, which was very much part of The Tatler’s appeal to both the readers and the advertisers.

This is not to suggest that the magazine did not engage with debates about gender roles. In many ways The Tatler, especially through the advertisements that it carried, maintained traditional gender ideals. Women were encouraged to wear cosmetics because it was ‘the duty of women to do everything to retain and preserve the beauty that Nature has given them’.[19] It was often traditional in the way that it reported domestic gender roles; for example, the descriptions of the renovations at Inveraray Castle in 1953 celebrated the taste of the Duke of Argyll, overlooking the important work of his wife in the transformations.[20] Theatre and cabaret reviews often had a slightly ‘leering’ tone, even when they written by women. A show at the Trocadero in the 1920s was described as featuring a procession of ‘lovely creatures’, and the dancers who portrayed enslaved girls in the show Chu Chin Chow were described as ‘London’s Prettiest’.[21] Likewise, the reporting of deaths during the First World War was also deeply gendered. The gossip columnist ‘Eve’ noted:

To die in the flower of their manhood, to fall in the shambles of war just when life is so full, so utterly worth living – for the women who have brought them to manhood, for those who are sharing it with them, it's almost too awful, too bitter to be borne, be the glory what it may.[22]

However, the ideals of the heroic male and the woman who needed to be protected were not always accepted. ‘Eve’ was critical of the way that women were presented in the case of Lieutenant Douglas Malcolm, who was cleared of the murder of ‘Count’ de Borch in 1917. Malcolm claimed self-defence and relied on the ideal of a ‘crime passionnel’, as de Borch, a womanizer and suspected German spy, had seduced Malcolm’s wife.[23] Describing it as an ‘amusing return to medievalism’, Eve noted that the case relied on ‘the delightfully masculine idea that man is the keeper of woman’s “honour”. As if a woman wasn’t quite capable of keeping anything she wanted to keep’.[24] Sometimes, those who transgressed gender norms were included. The male impersonator Vesta Tilley regularly featured in the magazine in its first two decades, and she was especially championed for her work in encouraging men to enlist through her act as an idealised British Tommy.[25] There were also fashion features that explored the ‘severely masculine mode’ of dress, and included advertisements of evening dress for women which featured a woman wearing a bow tie and holding a monocle.[26] Even those women who fitted the gender ideal of the age were used to sell goods beyond those closely associated with femininity; the image of a flapper was used to advertise sports equipment, cigarettes, and lawnmowers in the 1920s and 1930s.[27] Neither male nor female gender roles were static during the twentieth century, and in its reporting of elites, celebrities, and (sometimes) criminals, The Tatler did reflect this diversity of experiences.[28]

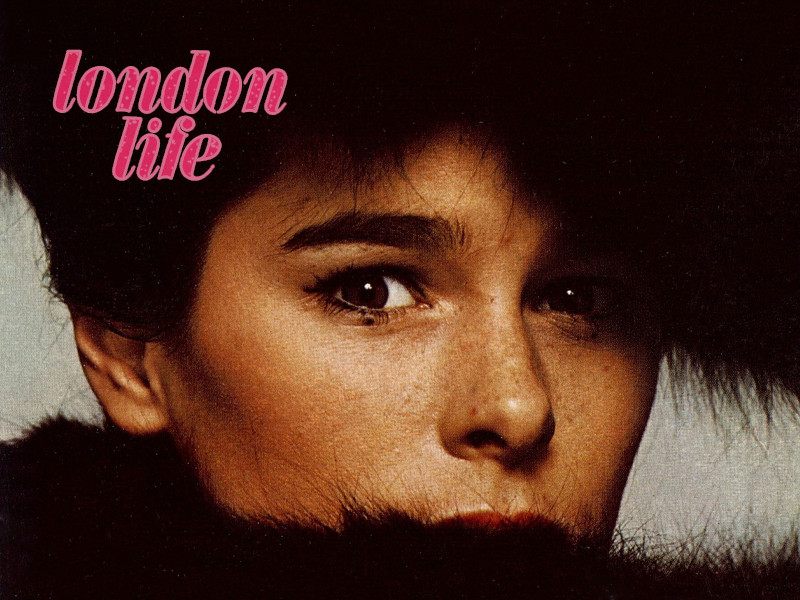

This diversity of experiences was especially notable in its reporting of significant social and political events. During the First and Second World Wars, The Tatler was keen to show its relevance beyond the social elite, and during the Great War it often featured soldiers on the front line, rather than global celebrities, on the cover.[29] Figures who had previously featured because of their sporting prowess, such as the tennis player Tony Wilding, were now included in lists of the war dead, and women like Lady Diana Manners were shown in their VAD uniform rather than in the latest fashions.[30] Likewise, the magazine charted the departure of aristocrats from their requisitioned country houses during the Second World War, as items were packed away to be replaced by hospital equipment, schoolgirls, or members of the armed forces.[31] However, in the wars, and their aftermath, there was still a strong emphasis on continuities. Although it has been estimated that roughly a sixth of country houses that were extant in 1900 were destroyed in the twentieth century, The Tatler championed those who found new solutions to retaining their stately homes.[32] For example, when Longleat House was first opened as a commercial concern in 1949, the Marquess and Marchioness of Bath featured on the front page, and their ‘public spirit’ was praised.[33] Likewise, while the London Season was changing there was still a strong sense of continuity in the reporting of elite life. Jennifer, the gossip columnist, argued that the end of the presentations at Court would not have that significant an impact on the Season, as it would ‘go on just the same’, like the aristocracy had been doing for many centuries.[34] It was really only once The Tatler encountered the social changes of the 1960s that its tone began to notably alter; in 1964 The Tatler’s owners sold the title and replaced it with the much more fashionable London Life in 1965.[35]

Despite its richness in visual materials and the social commentary it contained, especially in relation to gender, and the ways that it charted the changing nature of the social elite, The Tatler has not been fully explored by historians. In particular, although there has been excellent work in women’s and/or fashion magazines, the broader remits of ‘glossy magazines’, like The Tatler, have not had the same level of scrutiny. While focused on a very specific social class, it did have a wider readership, and its contents often reflected the desire of the aspirational middle classes, not just the realities of the featured social elite. In doing so, it became a location of consumption, of discussions about politics and current affairs, and the continuities and changes of gender and class ideals. This digitisation of the magazines means that the richness (in every sense of the word) of these pages is now available to a wider audience of scholars and readers to enjoy, examine, and explore.

[1] ‘Advertisement: The Tatler’, Country Life Illustrated, 9(234) (1901), p. xxxix.

[2] Sallie McNamara, Tatler’s Irony. Conspicuous Consumption, Inconspicuous Power and Social Change (London: Palgrave Pivot, 2018), p. 3; Janice Winship, Inside Women’s Magazines (London: Pandora, 1987), p. 27.

[3] Hannah Greig, The Beau Monde (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2013), pp. 6-9; Hannah Greig & Amanda Vickery, ‘The political day in London, c .1697–1834’, Past & Present, 252.1 (2021), pp. 101-37; Lucinda Gosling, Debutantes and The London Season (Oxford: Shire Library, 2013), pp. 6-11.

[4] Gosling, Debutantes, p. 13.

[5] The Tatler, 3 April 1963, noted in Gosling, Debutantes, p. 62.

[6] Adrian Tinniswood, Noble Ambitions: The Fall and Rise of the Post-war Country House (London: Jonathan Cape, 2021), p. 207.

[7] For example, ‘The Hunting and Shooting Season’, The Tatler, 18 December 1901; and ‘Where 3 hunts meet’, The Tatler, 18 December 1963.

[8] Tinniswood, Noble Ambitions, p. 186.

[9] For example, ‘The Annual Pilgrimage to Wimbledon’, The Tatler, 1 July 1936, p.20 ‘The Victors and The Vanquished’, The Tatler, 15 July 1964; Fiona Skillen, ‘“Woman and the sport fetish”: Modernity, Consumerism and Sports Participation in Inter-War Britain’, The International Journal of the History of Sport, 29:5 (2012), p. 758.

[10] Gaetano Cerchiello & José Fernando Vera-Rebollo, ‘From elitist to popular tourism: leisure cruises to Spain during the first third of the twentieth century (1900–1936)’, Journal of Tourism History, 11:2, (2019) p. 8; for example ‘The Caribbean Charted’, The Tatler, 20 November 1963.

[11] McNamara, Tatler’s Irony, p. 74; Kate Nelson Best, The History of Fashion Journalism (London: Bloomsbury, 2017), p. 87.

[12] Skillen, ‘Woman and the sport fetish’, p. 758.

[13] Tammy Clewell, ‘Fashioning identities through consumption: clothes, class, and gender in the first world war fictionalized epistolary column’, The Journal of Modern Periodical Studies, 10.1-2, (2019), pp. 5-6; Lucinda Gosling, Great War Britain. The First World War at Home (Stroud: The History Press, 2014), pp. 110-2.

[14] The Tatler, 13 November 1918, cited in Gosling, Great War Britain, p. 128.

[15] Best, The History of Fashion Journalism, p. 136.

[16] Best, The History of Fashion Journalism, pp. 74, 87.

[17] Howard Cox & Simon Mowatt, ‘Vogue in Britain: authenticity and the creation of competitive advantage in the UK magazine industry’, Business History, 54:1 (2012), p. 81.

[18] Cox & Mowatt, ‘Vogue in Britain’, p. 81.

[19] ‘Highway to Fashion’, The Tatler, 17 January 1917, cited in Gosling, Great War Britain, p. 127.

[20] Tinniswood, Noble Ambitions, p. 206.

[21] Cited in Thomas Harding, Legacy (London: William Heinemann, 2019), pp. 275-6; ‘The letters of Eve’, The Tatler, 13 September 1916.

[22] ‘Letters of Eve’, The Tatler, 9 September 1914, cited in Gosling, Great War Britain, p. 179.

[23] ‘The central figure of the greatest crime passional in the records of our courts’, The Tatler, 19 September 1917, p. 9.

[24] Eve, in The Tatler, cited in Gosling, Great War Britain, p. 193.

[25] For example, ‘Can women wear men’s clothes?’, The Tatler, 15 January 1908; ‘Miss Vesta Tilley’, The Tatler, 17 January 1917.

[26] The Tatler, 14 April 1926, reproduced in Laura Doan, ‘Passing fashions: reading female masculinities in the 1920s’, Feminist Studies, 24.3, (1998), fig 8.

[27] Skillen, ‘Woman and the sport fetish’, pp. 758-9.

[28] Matt Houlbrook, ‘Commodifying the self within: ghosts, libels, and the crook life story in interwar Britain’, Journal of Modern History, 85.2 (2013), pp. 321–63.

[29] For example, The Tatler, 22 December 1915; Gosling, Great War Britain, p. 7.

[30] Gosling, Great War Britain, pp. 17, 76.

[31] Caroline Seebohm, The Country House: A Wartime History, 1939-45 (London: Weidenfeld and Nicolson, 1989), pp. 14, 37.

[32] Giles Worsley, ‘Beyond the powerhouse: understanding the country house in the twenty-first century’, Historical Research, 78.201 (2005), p. 428.

[33] The Tatler, 6 April 1949, noted in Tinniswood, Noble Ambitions, p. 222.

[34] The Tatler, 3 April 1963, noted in Gosling, Debutantes, p. 62.

[35] Gosling, Debutantes, p. 62. The Tatler title was restored in 1968.

_1655826358-160x160.jpg)

.svg)