This article is part of an ongoing project to amplify other voices present in British Online Archives’ collections, particularly in archives relating to British colonial rule. Please note: some of these sources contain racist or offensive terms.

Over four centuries, an estimated 12–15 million African people were forcibly enslaved and transported from West Africa to the Americas. Their coerced labour was at the heart of a plantation economy that provided vast wealth and global influence for Britain and other nations. There is an abundance of excellent scholarship and resources relating to the horrors and injustices of transatlantic slavery and its legacies.[1] A relatively recent wave of research looks at lived experiences of transatlantic slavery, stressing the importance of piecing together individual histories from the archives. As Marisa Fuentes has asked, how “do we narrate the fleeting glimpses of enslaved subjects in the archives and meet the disciplinary demands of history?”[2]

British Online Archives (BOA) holds many thousands of record images relating to Britain’s involvement in transatlantic slavery. As part of our project to amplify marginalised voices in BOA’s collections, this article signposts some of the ways that these records can be reassessed and reframed to illuminate the lives of enslaved people. By their nature these histories are elusive. Surviving records were overwhelmingly written and created by those in positions of power: the plantation owners, merchants, slave ship captains, and traders who all played a part in the commodification of people.

However, in invoices, registers, accounts, logs, charts, and other records, the lived experiences of enslaved people are embedded in the written record. From these traces we can begin to build a picture of individual lived experiences of transatlantic slavery, from the point of embarkation on the West African coast, on the Middle Passage across the Atlantic Ocean, to the slave plantations of the Americas. We can highlight methods of resistance, and how the unfree had some agency (albeit in a fundamentally limited form) in shaping their own lives.

The Middle Passage

This was the journey of enslaved people across the Atlantic, from West Africa to the Americas. It was the “middle” leg of a broadly triangular route which transported European goods (guns, tools, cloth, brass and copper items, etc.) to trade in Africa; African people to work as slaves in the Americas; and colonial produce (sugar, rice, tobacco, indigo, rum, cotton, etc.) for sale in lucrative European markets. Routes varied, but the Middle Passage could last several weeks, aboard grossly overcrowded slave ships.

Documents from these journeys aid an understanding of the experiences of the enslaved. For example, ships’ logs show the practicalities of embarking and disembarking captives, the sales of enslaved people, and the names of those who purchased them. They may record attempted uprisings by the enslaved, which were not as unusual as might be expected.

British Online Archives (BOA), Slave Trade Records from Liverpool, 1754–1792, “Account book of the ship Fortune”, image 15.

This list of expenses for enslaved cargo on the British slave ship Fortune in 1805 helps us to build a picture of life on board for enslaved Africans sailing from the Congo River region of West Africa to Nassau in the Bahamas. Their limited diet was made up of plantains, boiled rice, yams, and “pease”. The latter refers to cowpeas, a non-perishable, nutrient rich food item widely available in West African ports. This constituted a major portion of the scant provisions given to enslaved African people.[3] A small amount of cod fish and beef is also recorded.

Sickness and disease were constant considerations for European merchants and traders, so there are also medical provisions in the expenses, such as the hire of a doctor, “port wine for sick slaves”, and rhubarb (primarily used for digestive complaints). Castor oil was known as a purgative, and was used to treat skin ailments and head lice. This regard for the health of enslaved people was not humanitarian: a human cargo was worth nothing until sold in the Americas. It was imperative, therefore, that slave ship captains kept the enslaved as healthy as possible (whilst still considering their profit margins).

Mortality rates were high, due to disease, violence, accident, and suicide. As part of keeping records of the human “stock” on board, ship records reveal individual tragedies. For example, this log (below) of 1789, from the British slave brig Ranger under Captain John Corran, contains typical mundane detail about the weather and the ship’s progress. Yet it also reveals an attempted suicide by an enslaved man who was being forcibly shipped from Annamaboe (in present day Ghana) to Jamaica.

British Online Archives, Slave Trade Records from Liverpool, 1754–1792, “Log of the brig Ranger”, image 10.

“Last night a man slave that slept in the boys room endeavoured to cut his throat with a knife or some other instrument and at day light when the hatch was taken off to get the tubs the same slave came upon deck and jumped overboard but was picked up with the boat and is in a fair way of recovery.”

Such a record is not uncommon: the instance of those forced to take, or who attempted to take, their own lives during the Middle Passage is striking. Many were unable or unwilling to cope with the trauma of the journey. Several African cultures held the belief that death would take them back to their homeland. Committing suicide was also an act of resistance. In a trade that commodified people, each enslaved person was of value. Those who managed to take their own life therefore reduced the profits of the voyage. For this reason, crews were keen to prevent suicides. Those who leaped overboard, like the man described in the source above, were often “rescued” by the ships’ boats.

Plantation slavery

Once disembarked and sold to a plantation, enslaved Africans faced a lifetime of forced labour for the cultivation of colonial products much in demand in Europe. For those who found themselves on plantations in the British West Indies, this invariably meant the production of sugar, a crop that required arduous and gruelling work to cultivate and process.

Plantations were businesses, as reflected in the administrative, financial, and legal nature of their records. Archives of the business of slavery can also offer glimpses into the lived experiences of the enslaved. Inventories of enslaved people appear alongside lists of livestock, tools, or crops produced for trade, a reminder of a system built upon the dehumanisation of people. Such records are limited in what they reveal about the enslaved, but they can offer us their names, ages, positions in the plantation hierarchy, and some detail about health.

British Online Archives, Antigua, Slavery and Emancipation in the Records of a Sugar Plantation 1689–1907, “Parham Register of Slaves Including Birth and Deaths, 1817–1826”, image 81.

This is a copy of the return made to the Slave Registry Office in Antigua of enslaved labourers on the Parham Plantation in October 1817. It describes individuals of African descent whose names have been, largely speaking, removed—part of a process by which enslaved people were detached from their origins. Enslaved labourers were usually assigned anglicised names; Greco-Roman names were also common, as were names relating to places.

Here, too, we see some of the ailments that afflicted the enslaved, including consumption (a pulmonary disease), dropsy (swelling), rheumatic disease, lumbago, and arthritis, all suggestive of the physical impact of field work on joints and muscles. The third entry in the above source informs us that Phibba worked in the “field when well”, a further indication that conditions on plantations were often debilitating.

Everyday resistance

Plantation records also grant insights into forms of resistance. That the enslaved should resist a culture of violence and terror is not surprising. As scholars have argued, the “entire history of slavery and the Atlantic slave trade was characterised by slave resistance of one form or another”.[4] Everyday resistance was covert and aimed at undermining, rather than overthrowing, slavery. It included tactics such as stealing, damaging equipment and property, deliberately working slowly or poorly, or feigning illness. Such everyday forms of resistance sought to disrupt the workings of the plantation.

An example of working in a disruptive manner can be found in the letters of Thomas Barritt, the manager of Jamaican estates owned by Nathaniel Phillips. Phillips was a sugar merchant, planter, and later absentee owner of several slave plantations in Jamaica (the largest and wealthiest of the British Caribbean islands). In January 1796, Barritt wrote about the need for improvements on the Phillipsfield estate, specifically highlighting the behaviour of “a bad disposed Driver”, named Pera. A “Driver” was an enslaved man appointed to direct the work of the field labourers. Drivers had a higher status within the hierarchy of the enslaved population. Like stock keepers, sugar processors, distillers, carpenters, and those perceived as more skilled, they had a higher value to the estate. Consequently, they received better accommodation and provisions.

British Online Archives, Slavery, Exploitation and Trade in the West Indies, 1759–1832, “Letters, 1796 Oct. 14 to 1800 Dec. 4”, image 1.

“I am well assured that a great part has been occasioned from a bad disposed Driver (Pera), who was when you left this country a very good n— & continued so for some time after, but when he took to drinking, often came into faults, and when punished, got dejected, and was very impudent to the whites. It was then noticed that the n— did not work in their usual way, and many of them took to sculking, and others to drinking, which occasioned much loss of labour on the Estate!”

Pera, it was alleged, was behaving with disruptive and disorderly intentions, and encouraging others to do the same. Later, Barritt reported how a stock of “very indifferent sugar” had been processed, although “the canes were as good as ever I saw”. Pera was suspected of having “poisoned” the production process. All of this, as Barritt noted, led to loss of labour on the estate, and had an impact on profitability.

What can we conclude about the life of Pera? We know that Nathaniel Phillips had plantations in St. Thomas in the East, a parish in Jamaica. James Pinnock was Phillips’s lawyer. In 1796 Pinnock also owned a plantation there, named Pera.[5] We can assume that Pera’s given name means that he was originally purchased to work on this plantation. To be a driver imparted a conflicted status: still enslaved, but given the responsibility to direct the work of others (often cruelly, with whips involved). Perhaps this explains Pera’s drinking, but gaining knowledge of the position he held also helps us to understand how he was influential on the estate.

Another form of resistance to plantation slavery was self-harm, whereby the enslaved deliberately removed themselves from the labouring needs of the estate. Other business records in the Phillips papers include inventories which record the “increase and decrease of N—” on an estate, reflecting births and deaths in the enslaved population. The dehumanisation of the enslaved is clear, as they are considered property to be accounted for.

British Online Archives, Slavery, Exploitation and Trade in the West Indies, 1759–1832, “Records, 1789–1812”, image 243.

Grafton, who worked on the farm at Pleasant Hill, died in 1791. In the above source he is described as “bloated, a dirt eater”. Scholars have discussed the significance of eating non-food items, usually dirt, regarding it as a response to deficiencies in the diet of the enslaved. Some have also argued that in affecting the productivity of the plantation by removing themselves from the workforce, it was a form of passive resistance: “a means of negotiating power for the powerless”.[6]

Within the records of plantation slavery there is also much evidence of the enslaved escaping or running away. A whole series of laws and enactments were introduced with the aim of preventing runaways, such as this Act (below) from Dominica in 1773. Similarly, newspapers from the period displayed numerous notices about runaway slaves, demonstrating the frequency of this act of resistance.

British Online Archives, American Records in the House of Lords Archive, 1621–1917, “West Indies Slaves, 1792–1799”, image 13.

The enslaved might run away to escape the conditions of life on their plantation, or to reunite with friends and families on neighbouring plantations. Others used it to change their owners or to make life more bearable for a while.

British Online Archives, American Records in the House of Lords Archive, 1621–1917, “Judicial proceedings with regard to slaves 1819, part 2”, image 39.

These court records from 1817 describe the various offences of enslaved people tried in Jamaican Assize Courts. York, Charlton, and William were charged with being “notorious and incorrigible runaway[s] and frequently running away”. Running away was not always an individual act. William was charged with “harboring a runaway slave”, suggesting that there were covert networks of support and assistance in play.

Overt Resistance

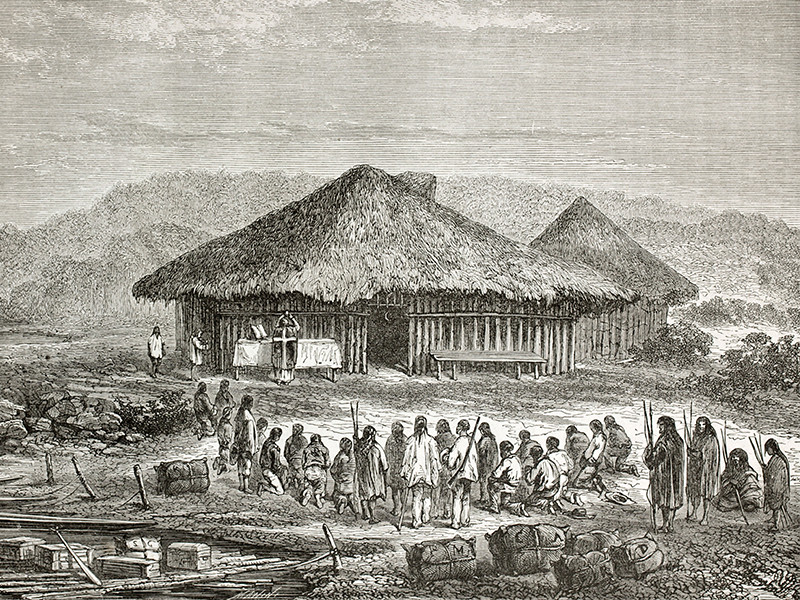

Leonard Parkinson, Maroon leader, Jamaica, 1796.

There is evidence of sufficiently large communities of runaways to prove that many were able to create new lives for themselves. Maroons were freedom fighters, a mixture of indigenous islanders and runaway enslaved people who escaped to live in freedom in the mountains or tropical terrains of the Caribbean. The word derives from the Spanish “Cimarron”, which means “wild” or “untamed”. For over 80 years, the Maroons of Jamaica formed communities in the mountains, mounted raids on plantations, and lived free from British rule. They were at war with the British army from 1728. A peace treaty in 1739 gave the Maroons some land in return for a promise not to take in runaways. A second war took place from 1795–1796. This was reported by Thomas Barritt in a letter sent to Nathaniel Phillips in January 1796. Barritt described British forces “extinguishing the embers of this rebellion”.

British Online Archives, Slavery, Exploitation and Trade in the West Indies, 1759–1832, “Letter dated 29 January 1796”, image 6.

However, a later letter from that year reported “mischief” and “alarming cases” of fires on Jamaican estates which had damaged the sugar crop.[7] The letter refers to “some evil minded, or Runaway people, setting fire to Stoakes Hall canes”.[8]

Fears were stoked by the only successful revolt of enslaved people in the Caribbean. This began in the French colony of Saint Domingue in 1791. BOA collections contain reports on “the very alarming insurrection of the N—” from the General Meeting of West India Planters in November 1791.[9] Their greatest fear was the “dreadful consequences” of news of successful rebellion spreading to Jamaica, the nearest British colony, and “that attempts have been made and are still making to create and ferment in the minds of the N—in our colonies a dangerous spirit of innovation”.[10]

There were several subsequent attempted plots and revolts by the enslaved against British rule, such as in Barbados in 1816, and in Demerara in 1823. One of the largest uprisings occurred in Jamaica in 1831 when over 60,000 enslaved people under the Baptist preacher Samuel Sharpe revolted against labour shortages and other grievances. 200 enslaved people were killed during this rebellion. A further 300 were executed after the revolt was put down.

Rumours of plots and imaginary threats reflected planters’ deep-seated fear and distrust of their enslaved workers. We don’t know much more about the detail of this alleged plot in Jamaica in 1816 which is recorded in judicial proceedings (below).

British Online Archives, American Records in the House of Lords Archive, 1621–1917, “Judicial proceedings with regard to slaves 1819, part 2”, image 20.

This group of enslaved people from the estate of George Phillips—named as Francis alias Davy, King Robert alias Congo Robert, Mingo alias Rodney, Jenning alias Harry Henry, Andrew Turnbull, Ben, Allick alias Congo Allick, and Davy alias Mungola Davy—were accused of “riotously assembling and gathering together”, and of assaulting property, white workers, and “sundry slaves”.

Sometimes, like in this case, the enslaved resisted openly, collectively, and violently. Other forms of agency and resistance were more subtle. This brief survey of records shows that the power map of slavery is complex. While owners of the enslaved exercised extreme and often violent control over the lives of their captive labourers, the enslaved did control some aspects of their lives. As this article has demonstrated, enslaved people had some limited means of strategically affecting and ameliorating their conditions. Traces of the lived experiences of the enslaved are elusive, but illuminating them is possible and doing so helps us to better understand their lives, and to celebrate their bravery.

Further research in BOA collections:

The transatlantic slave trade

- Slave Trading Records from William Davenport, 1745–1797

- Slave Trade Records from Liverpool, 1754–1792

- Scottish Trade with Africa and the West Indies in the Early 18th century, 1694–1709

- Liverpool Through Time: From Slavery to the Industrial Revolution, 1766–1900

- American Slave Trade Records and Other Papers of the Tarleton Family, 1678–1838

- Power and Profit: British Colonial trade in America and the Caribbean, 1678–1825

- American Records in the House of Lords Archive, 1621–1917, including records of the Royal African Company

- Slavery in Jamaica, Records from a Family of Slave Owners, 1686–1860

- Slavery, Exploitation and Trade in the West Indies, 1759–1832

- Antigua, Slavery and Emancipation in the Records of a Sugar Plantation, 1689–1907

- American Records in the House of Lords Archive, 1621–1917

- Slavery Through Time: from Enslavers to Abolitionists, 1675–1865

Emancipation in 1834, and after

- Slavery in Jamaica, Records from a Family of Slave Owners, 1686–1860

- Slavery Through Time: from Enslavers to Abolitionists, 1675–1865

- Antigua, Slavery and Emancipation in the Records of a Sugar Plantation, 1689–1907

- Caribbean Colonial Statistics from the British Empire, 1824–1950

Records of missionaries active in the British Caribbean

- The West Indies in Records from Colonial Missionaries, 1704–1950

- Colonial Missionaries Papers from America and the West Indies, 1701–1870

[1] As a starting point, please see http://www2.vcdh.virginia.edu/bib/index.php. For digital sources, https://www.slavevoyages.org/ is an excellent example.

[2] Marisa J. Fuentes, Dispossessed Lives: Enslaved Women, Violence, and the Archive (Pennsylvania: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2016).

[3] Benjamin Torke, “Cowpeas and the African Diaspora”, available at https://www.nybg.org/planttalk/tag/cowpeas/.

[4] Gad Heuman and James Walvin (eds), The Slavery Reader (Oxon: Routledge, 2003), 545.

[5] “Old and New Pera”, Centre for the Study of the Legacies of British Slavery, available at https://www.ucl.ac.uk/lbs/estate/view/3057.

[6] Michelle Gadpaille, “Eating Dirt, Being Dirt. Backgrounds to the Story of Slavery”, AAA: Arbeiten aus Anglistik und Amerikanistik 39, no. 1 (2014): 3–20.

[7] British Online Archives, Slavery, Exploitation and Trade in the West Indies, 1759–1832, “Letter dated 20 May 1796”, available at https://microform.digital/boa/documents/164/letters-1796-oct-14-to-1800-dec-4, image 29.

[8] Ibid.[9] British Online Archives, Slavery, Exploitation and Trade in the West Indies, 1759–1832, “Reports, 1791 March 1–30”, available at https://microform.digital/boa/documents/259/reports-1791-march-1-30.

[10] Ibid.

.svg)