The publication of this article coincides with the release of a new collection by British Online Archives (BOA), Radicalism and Popular Protest in Georgian Britain, c. 1714–1832. Providing access to more than 90,000 digitised images from the holdings of The National Archives (UK) and the Working Class Movement Library (UK), this resource allows researchers to trace, in unprecedented detail, the shifting language and practice of political dissent—from the Jacobite mobs of the 1710s to the mass reform movements of the early nineteenth century.

In the early Georgian period, the dominant oppositional ideology was Jacobitism—an essentially backward-looking credo that sought the return of the Stuart monarchy. Over time, however, more progressive and “radical” ideas came to the fore. By the close of the Georgian era, new voices—journalists, artisans, and reform societies—were shaping political debate and demanding that the “rights of man” be recognised by parliament. This article sketches out this transformation whilst highlighting the kind of material available in BOA’s new collection.

The Challenge of Jacobitism

During the reigns of King George I (1714–1727) and King George II (1727–1760), no such thing as a “political radical” existed in the British lexicon. The entry for “radical” in Samuel Johnson’s Dictionary (first published in 1755) makes no connection between that word and politics. Instead, contemporaries deployed the phrase most frequently in a medical context, particularly when referring to a “radical cure” capable of returning a sick patient to their original state of health—as Johnson pointed out, the root of “radical” was radix meaning source or origin.[1] Only much later in the century did those who proclaimed the need to restore the British constitution to its “original” (and semi-mythic, proto-democratic) state begin to refer to themselves as “radicals” or “radical reformers”.[2]

This is not to imply that social relations before 1760 were quiescent, for they rarely were. The early Georgians were familiar with large-scale protests (particularly food riots, anti-tax, and anti-recruitment riots). As such, they were attuned to the power of the “mob’”—the pejorative word that elites and the middling sorts used to describe large groups of people in movement and in protest (the phrase derived from mobile vulgus: the movable or excitable crowd).[3] Given the centrality of collective protest within Georgian social life, the elderly Duke of Newcastle (1693–1768) was only half joking when he said in 1768: “I love a mob. I headed a mob once myself. We owe the Hanoverian succession to a mob.”[4]

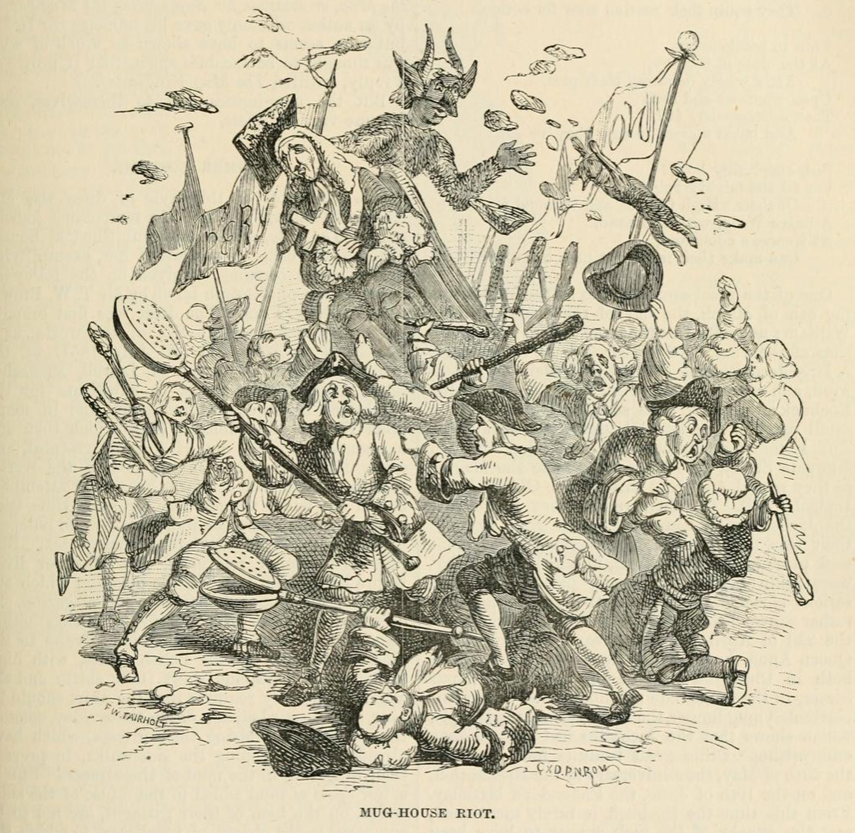

In fact, Newcastle (then 75 years old) was reflecting on the intensive urban riots of fifty years earlier, when rival “mobs” vied for spatial dominance over the streets of Westminster in a proxy war between the new Hanoverian regime (which had the support of the Whigs) and the deposed Stuart monarchy (which still claimed the allegiance of many Tories). The “mug house” riots of 1715 and 1716 saw pro-Hanoverian loyalists issuing out of taverns (“mug houses”) armed with cudgels to meet rival bands of Jacobite demonstrators—i.e. those who wished for the return of the Stuarts. Newcastle, then 21 and Lord Lieutenant of Middlesex, was directly involved in bankrolling and organising the paramilitary Loyal Societies. On one occasion (17 November, 1715)[5], he personally led a band of loyalists in violent confrontation with a Jacobite “mob” that was attempting to burn effigies of George I.[6] The “mugs” succeeded in confiscating the effigies, but not before Newcastle had been separated from his companions and was forced to make his escape over some rooftops and through the house of a cheesemonger of Money Lane Alley!

[A Victorian representation of a mug house riot taken from Robert Chambers, The Book of Days (London, 1888), 111.]

[A Victorian representation of a mug house riot taken from Robert Chambers, The Book of Days (London, 1888), 111.]

Whig ministers, who lived through the turbulence of the Hanoverian accession and governed Britain for the next four decades, lived in fear and expectation of a major Jacobite outbreak. As documents from the State Papers (SP) series at The National Archives (TNA) demonstrate, the Secretaries of State for the Northern and Southern Departments (forerunners of the Foreign Office and Home Office respectively) received large numbers of reports informing them that popular support for the deposed Stuarts was rife. The son of King James II, James Francis Edward Stuart (1688–1766) was viewed by his supporters as the rightful heir to the English and Scottish thrones but was labelled “the Pretender” by loyalists and the British state.

Jacobitism thus became a major political fault line in these years with even the gentry—the wealthiest five per cent of the population who monopolised land ownership and positions of authority—sharply divided over this fundamental dynastic question. This divergence among the “rulers of the countryside”, in turn, made enforcing wider social conformity to the Hanoverian succession extremely difficult.

For instance, in 1719, Thomas Hartopp, a magistrate of Leicestershire and loyal servant of George I and his Whig ministers, struggled to bring prosecutions against twenty locals who had celebrated the Pretender’s birthday with a rowdy gathering in Loughborough culminating in the firing of a gun. He complained that such open acts of disloyalty were:

[O]wing to a neglect or rather disloyalty of our justices of the place who laugh at all complaints that are made to them (of this kind)[,] one Mr Phillips a neighbour justice of the peace will never hear any of these complaints which makes them bolder and throws the odium of the party on me [. . .] I need not tell your Lordship how disaffected the Gentlemen of this country are, indeed, I believe they are the worst in England."[7]

The following year, Hartopp reported the disloyalty of one “Kimsey”, a local man who had married into money and insisted on publicly wearing “a White Rose in his bosom” as a symbol of his support for the Jacobite cause. He was also “heard to say that [. . .] the Crown be the Pretender’s right”. Hartopp requested help from the Attorney General to bring Kimsey to justice, stating that “if there is not an example or two made, they begin to be barefaced, he is a professed Jacobite and truly there is so many of them in this part of the Country that I have much a doe to deal with them”.[8]

Popular Jacobitism was also strong in the Scottish borders. During the rebellion of 1745–1746, five days before Hanoverian and Stuart troops did battle on the field of Culloden (16 April, 1746), the Secretary of State was forwarded an affidavit from Hexham (Northumberland) which gave an account of a plot got up by “sixteen gentlemen” of that country to lead “Fifteen Hundred Men” to seize control of Newcastle. The bulk of the support was said to come from the “keelmen” (i.e. the boatmen employed transporting coal down the Tyne), who had a fearsome reputation for their ability to organise collectively. The plan was to “take the Cannon in the Town and carry it off” before joining the rebellious Highlanders.[9]

Sir Edward Blackett wrote to the Mayor of Newcastle to warn him of the “intention of several disaffected Persons to Rise in Rebellion”. Security in the town was tightened accordingly.[10] On the evening of 18 April, finding that Sandgate Gate was locked and soldiers were standing guard, forty keelmen informed the soldiery that if they were not let through ‘”they would find a Body of men and axes to make a passage for themselves”. They damned the Mayor to “hell” and warned that they would be back in two days’ time to “drive the [. . .] regiment out of town" pledging to “make a Sherrifmoor of it”.[11]

Yet the Jacobites never did take Newcastle, and their Highland troops were decisively defeated by those of the Duke of Cumberland—now nicknamed “the butcher of Culloden”.[12] That defeat opened the door to reprisals and confiscations exacted by the victorious Hanoverian regime on the defeated supporters of the House of Stuart. From 1746 until the death of the “Young Pretender” (Charles Edward Stuart, b. 1720) in 1788, Jacobitism limped on, but it ceased to pose an existential challenge to either the government or the monarchy and its popularity in Britain diminished precipitously.

Wilkes and Liberty

By the reign of King George III (1760–1820), the contours of political contention were shifting. Attempts by the British government to levy new duties, like the Stamp Tax (1765), on the thirteen colonies in North America led to protests and a boycott of British goods.[13] In Britain, meanwhile, soaring food prices caused subsistence riots and industrial unrest that ran alongside an explosion of heated debates around “English liberty”. At the epicentre of these controversies was John Wilkes (1725–1797), often considered the “original English radical”.[14]

Wilkes was an ardent critic of the Stuarts, whom he saw as absolutists.[15] At the same time, he viewed George III’s “favourite” minister, the Scotsman John Stuart, third Earl of Bute, as cut from the same tyrannical cloth. He launched a series of searing attacks on the Bute ministry (and by extension the king) in his opposition journal, North Briton. Famously, issue no. 45 (April 1763), in which Wilkes criticised the king’s recent speech to parliament, landed him in hot water. Forty-eight printers suspected of circulating the text, as well as Wilkes himself, were arrested under a “general warrant”.

Earl Halifax, Secretary of State, judged the forty-fifth number of North Briton to be a “most insolent, and libellous Invective upon the King’s Speech” while the Attorney General and Solicitor General moved to prosecute its authors and publishers for seditious libel.[16] There was no disputing Wilkes’ involvement.[17] However, he managed to turn his subsequent trial to his advantage. At the Court of Common Pleas, Wilkes made several grandstanding speeches in which he claimed that general warrants (which named neither the accused nor their alleged offence) were an unconstitutional invasion of the rights of the freeborn Englishman.

Chief Justice Pratt (one of Wilkes’ many sympathisers) skirted the issue of general warrants but ruled that as the libel was not a breach of the peace and as Wilkes was the sitting MP for Aylesbury, he was entitled to the privilege of parliament and must be discharged. A jubilant crowd escorted Wilkes home to St George Street, Westminster, chanting “Wilkes and Liberty”—a slogan that was heard with growing frequency in subsequent years. Parliament took a far dimmer view of Wilkes’ exploits and promptly dismissed him from the Commons before issuing a writ of outlawry that sent him into exile.

After racking up substantial debts in Paris, Wilkes took an extraordinary gamble by returning to stand in the general election of 1768. Unexpectedly, he romped to victory in Middlesex, a constituency with a remarkably large and open franchise.[18] Notwithstanding his status as an outlaw, Wilkes marshalled considerable support among the shopkeepers, artisans, and journeymen in Middlesex and beyond. Raucous celebrations followed in both Brentford, where the polling had taken place, and London. The number “45” was chalked on walls and carriage doors, chants of “Wilkes and Liberty” were got up by drunken revellers, and at midnight a “mob of about 100 Men and Boys” toured the streets of the West End, “putting in” the windows of well-to-do houses whose owners had failed to illuminate them in support of their hero.[19]

[British Museum, M.4744, Medal commemorating John Wilkes, “Genius of Liberty” and “Knight of the Shire” for Middlesex (1768), © The Trustees of the British Museum. Shared under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0) licence.]

[British Museum, M.4744, Medal commemorating John Wilkes, “Genius of Liberty” and “Knight of the Shire” for Middlesex (1768), © The Trustees of the British Museum. Shared under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0) licence.]

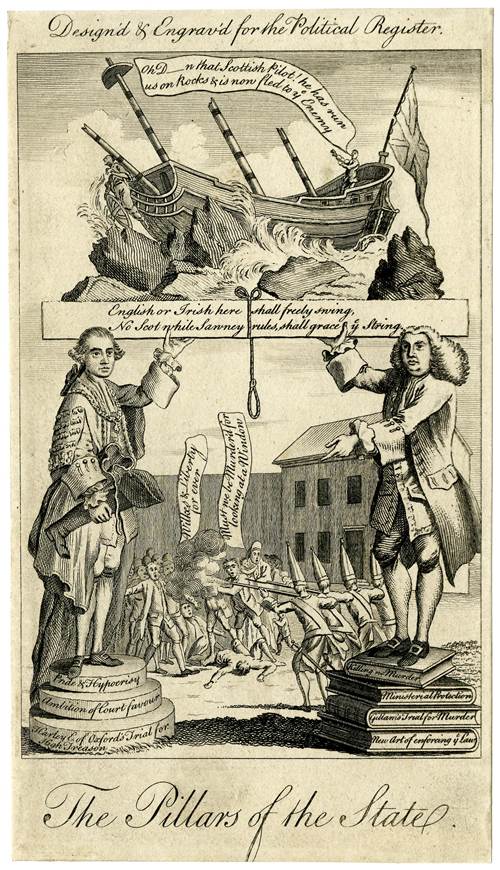

Wilke’s next move was to hand himself in to the Court of King’s Bench where Lord Mansfield remanded him to the King’s Bench prison. On 10 May, a “prodigious concourse of disorderly people” gathered in St George’s Fields in support of Wilkes. The crowd pressed so hard against the prison walls that they “burst open the outward gate”. Wilkes urged them to disperse but neither he nor two magistrates armed with the Riot Act could persuade them to do so. A small company of Scots Guards were pelted with stones and Justice Gillam was struck on the head before he gave orders for the soldiers to fire.[20] Six people were killed and fifteen wounded in what became known as the “Massacre of St George’s Fields”. The episode generated reems of negative press for the army and the government but cemented Wilkes’ reputation as the “champion of freedom”.[21]

[British Museum, Satires, 4235, Anon., The Pillars of the State (1768), © The Trustees of the British Museum. Shared under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0) licence. It criticised Justice Gillam (right) and the Scots Guards (centre) for their role in the “Massacre of St George’s Fields”, 1768.]

[British Museum, Satires, 4235, Anon., The Pillars of the State (1768), © The Trustees of the British Museum. Shared under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0) licence. It criticised Justice Gillam (right) and the Scots Guards (centre) for their role in the “Massacre of St George’s Fields”, 1768.]

In February 1769, the Commons finally took the decision to overturn the Middlesex election result, expelling Wilkes from parliament for a second time. Undeterred, the voters of Middlesex re-elected the imprisoned Wilkes in three successive elections (those of February, March, and April 1769) in defiance of a recent Commons ruling that held him to be “incapable” of taking a seat in the House. In the last of these contests, Wilkes received 1,143 votes to 296 for his opponent. Nevertheless, parliament determined that the defeated Henry Luttrell was duly elected for Middlesex. After his release from prison (April 1770) and his successful election as Lord Mayor of London (1774), Wilkes was once again returned (this time unopposed) as MP for Middlesex, with parliament finally conceding that he could take his seat in the Commons.

Whilst acknowledging his unappealing traits, such as his debauchery, chauvinism, and self-interestedness, historians have also praised Wilkes’ uncanny ability to bring to the fore many important questions of civil liberty, including the use of general warrants, the freedom of the press to report on parliamentary business, and the right of electors to choose their representatives. In his first decade as MP for Middlesex, Wilkes advocated for shorter parliaments, the exclusion of placemen and pensioners from the House, and for parliamentary reform.[22]

His methods of political communication were also novel. As John Brewer has shown, Wilkes understood the value of publicity and ensured that his distinctive squinting visage was reproduced on a wide variety of commercially available products including teapots, snuffboxes, and medals.[23] These were displayed and shared by his supporters helping to further cement his popular acclaim.[24] Moreover, the slogan “Wilkes and Liberty” travelled far and wide and signalled the desire shared by Wilkes and his supporters to “[open] wider the channels of communication between parliament and the 'political nation’ out-of-doors”.[25]

“Members Unlimited”

Once ensconced in power, however, Wilkes allowed his radicalism to ossify, and he quickly became, in his own words, an “extinct volcano”.[26] He finally retired from parliament in 1790, just as the French Revolution (which broke out in 1789) was energising a new generation of radicals, whose ambitions for thoroughgoing political reform were on a scale that dwarfed even those of Wilkes.

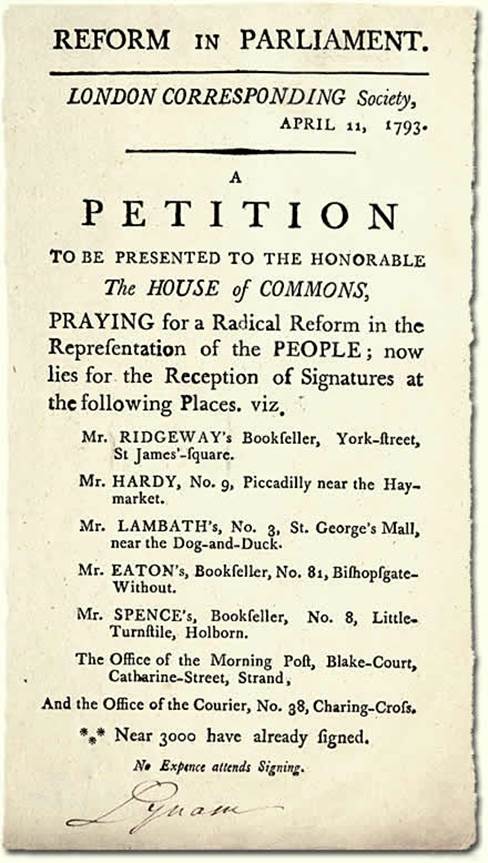

Partly inspired by the birth of a new French Republic, partly in response to the publication of Thomas Paine’s Rights of Man (March 1791 and February 1792), the London Corresponding Society (LCS) was established in January 1792 by a group of plebeian Londoners led by Thomas Hardy, a Scottish shoemaker residing in Piccadilly. A reflection of the artisanal background of many of its early leaders, membership of the LCS was “unlimited”—that is, open to men of all social classes.

The club sought to create a federation of “corresponding societies” throughout the country as a means of raising the political consciousness of the public. Their goal was to build popular momentum behind the demand for a “radical reform of parliament”.[27] What this meant, in essence, was universal manhood suffrage—one man one vote. This was a form of government that Paine had advocated in 1792 and which the French Constitution had proclaimed in 1793.[28] Through an extension of voting rights, the LCS argued that the “the voice of the people” would, for the first time, be “heard in the councils of the nation”.[29]

[TNA, TS 24/3/34, An LCS handbill advertising a petition for “Radical Reform” of parliament (April 1793). The earliest mentions of “radical” politics come from LCS literature of this period.]

[TNA, TS 24/3/34, An LCS handbill advertising a petition for “Radical Reform” of parliament (April 1793). The earliest mentions of “radical” politics come from LCS literature of this period.]

Unfortunately for the LCS, the upheavals in France reduced the chances of British radicals obtaining constitutional reform at home. The execution of King Louis XVI (January 1793), followed by Britain’s declaration of war against France, and the forced displacement of 30,000 Roman Catholic priests (1789–1799) generated considerable alarm among Anglican clergy and British politicians. With elite fears of bloodshed and anarchy running at fever pitch, persuading parliament to alter the fundamentals of the British political system was next to impossible.

Instead, the LCS was viewed from Whitehall as a potentially dangerous domestic branch of the Jacobin club. Their members were spied upon intensively and their leaders became the focus of government legal repression. The Home Office had no difficulty getting word of what had passed at radical debates and public demonstrations, but they found that the services of paid agents were needed to infiltrate private LCS divisional meetings.[30]

Armed with the testimony of its spies, the government launched prosecutions, first against the Scottish reform association—the Society for the Friends of the People (1793–1794) and then against the LCS itself in 1794. Five “Scottish Martyrs” were tried and sentenced to long terms of transportation to the penal colony in Botany Bay.[31] The treasons trials against Thomas Hardy, John Thelwall, and others eventually collapsed. [32] However, the LCS continued to be closely watched by the government and hounded by loyalist “mobs” until it was finally banned by name in 1799.[33]

[BOA, “FRAMED/058: London Corresponding Society, Alarm'd”, 1798. James Gillray’s depiction of an LCS divisional meeting reading about the latest round of “state arrests”.]

[BOA, “FRAMED/058: London Corresponding Society, Alarm'd”, 1798. James Gillray’s depiction of an LCS divisional meeting reading about the latest round of “state arrests”.]

By closing down space for discussing political reform, the government drove moderate radical leaders into early retirement and inadvertently encouraged the emergence of a “revolutionary underground” led by “ultra-radicals”. From the later 1790s, the British state experienced a succession of subversive challenges—beginning with the naval mutinies at the Nore (1797)—during which it emerged that members of the ultra-radical group, the “United Britons”, had infiltrated the Royal Navy. This was followed by the rebellion instigated by the United Irishmen (1798), the Despard Conspiracy (1802), and Robert Emmett’s Rebellion (1803).[34]

Although revolutionary plots continued to be uncovered in the years following the peace of 1815, the temporary relaxation of proscriptions on free speech and free assembly allowed the constitutionalist arm of the reform movement to revive itself. In this postwar period, when the cost of living was mounting and industry depressed, journalists like William Cobbett (1763–1835) and Richard Carlile (1790–1843), along with orators such as Sir Francis Burdett (1770–1844) and Henry Hunt (1773–1835), were able to build mass support for reform among working people in London and the industrialising north.

[British Museum, Satires, 12869, George Cruikshank, The Spa Fields orator Hunt-ing for popularity to Do-good!! (1817), showing a reform meeting at Spa Fields, March, 1817, © The Trustees of the British Museum. Shared under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0) licence.]

[British Museum, Satires, 12869, George Cruikshank, The Spa Fields orator Hunt-ing for popularity to Do-good!! (1817), showing a reform meeting at Spa Fields, March, 1817, © The Trustees of the British Museum. Shared under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0) licence.]

The Lancashire-born weaver, Samuel Bamford (1788–1872), recalled that when he was a lad in the 1790s his father had been one of a select “band [. . .] of readers and inquirers" in the town of Middleton who had read the works of Thomas Paine:

They were called 'Jacobins' and 'Painites' and were treated with much obloquy by such of their bigoted neighbours."[35]

By the time he reached his thirties in the 1810s, however, radicalism had become mainstream. In August 1819, Bamford proudly led 3,000 of his fellow townspeople (including 200 women) to “the most important meeting that had ever been held for Parliamentary Reform”.[36] The procession, which marched with “steadiness and seriousness” carried with them coloured banners embroidered with the slogans "Unity and Strength”, “Liberty and Fraternity”, “Parliaments Annual”, and “Suffrage Universal”.[37]

[TNA, MPI 1/134/18, Evans and Sons, A Meeting of the Radical Reformers (1819)—an engraving of the forcible dispersal of the reform meeting in St Peters Field, Manchester.]

[TNA, MPI 1/134/18, Evans and Sons, A Meeting of the Radical Reformers (1819)—an engraving of the forcible dispersal of the reform meeting in St Peters Field, Manchester.]

At St Peter’s Fields the peaceful demonstration of 60,000 was brutally suppressed by local magistrates who ordered the Manchester and Salford Yeomanry to charge the crowd with their sabres drawn. Eighteen fatalities followed with nearly 700 injured.[38] Hunt, Bamford, and eight others were initially held on treason charges but were later indicted for sedition and unlawful assembly. After some delay, they (along with three other defendants) were convicted of the lesser crime of seditious intent and were confined in separate prisons.[39] In the short term, the incarceration of key leaders was a disaster that left the radical movement in disarray.

Over the longer term, however, as journalists spread news of the “Peterloo Massacre” far and wide, its memory became a powerful tool in the arsenal of radicals who sought to both critique aristocratic “misrule” and win over the middle classes to the cause of reform. Although a clutch of new repressive laws silenced the radical press and prevented mass meetings for a time in the early 1820s, the ground was well-prepared for a broadly-based, cross-class radical movement to emerge at the end of the decade.

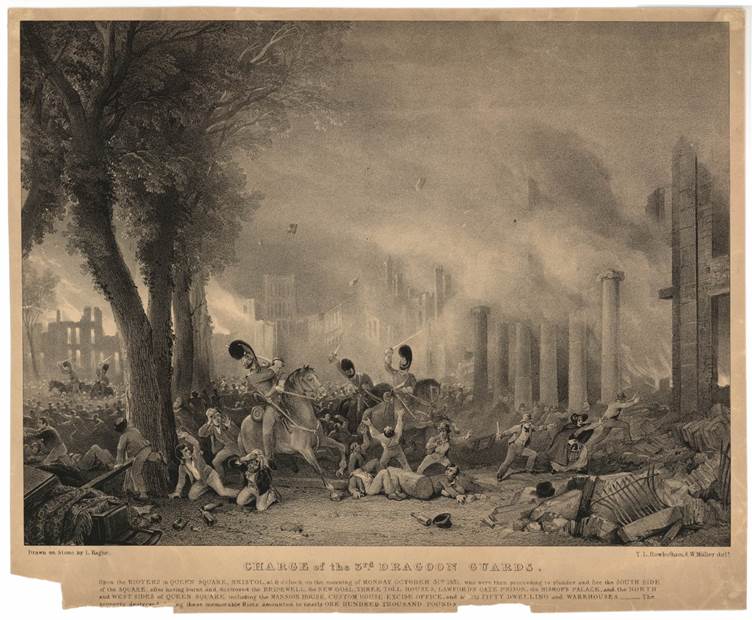

The Great Reform Act of 1832 was the fruit of an intensive period of radical agitation, which saw reformers protesting vigorously against the attempts of the House of Lords to block an extension of the franchise. Middle- and working-class radicals were temporarily united in new societies like the Birmingham Political Union. However, the most explosive manifestation of the clamour for reform was at Bristol in October 1831, when Queen’s Square was razed to the ground and Peterloo reenacted by regiments of Dragoons who cut down demonstrators in their dozens.[40]

[British Museum, 1871, 0812.5330, L. Haghe, Charge of the 3rd Dragoon Guards Upon the Rioters in Queen Square Bristol (1831), © The Trustees of the British Museum. Shared under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0) licence.]

[British Museum, 1871, 0812.5330, L. Haghe, Charge of the 3rd Dragoon Guards Upon the Rioters in Queen Square Bristol (1831), © The Trustees of the British Museum. Shared under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0) licence.]

When it eventually passed into law the following year, the Reform Act did away with corrupt “pocket boroughs”, granted parliamentary representation for the first time to densely populated industrial towns like Birmingham and Manchester, and doubled the franchise to include one in five men.[41] These were major achievements that the radical reform movement had fought hard to place on the political agenda. However, the Act also left much undone.

Most importantly, the Whigs, led by Lord John Russell (1792–1878), had carefully framed the Reform Act to exclude working-class men from exercising the right to vote. Middle-class radicals may have had cause to celebrate but the scene was now set for the emergence of a working-class reform movement. Between 1838–1851, the Chartists—whose first demand was “one man, one vote”—took up this mantle and British radicalism entered a more class-conscious and conflictual phase. As Malcolm Chase and others have pointed out, Chartism was a truly mass political movement, involving the active participation of millions of men, women, and children.[42] One of its greatest achievements was in uniting the constitutionalist and ultra-radical strands of working-class radicalism behind the demand for the People’s Charter.

Conclusions

By the time of King William IV’s reign (1830–1837), Britain’s oppositional politics had travelled a remarkable distance. Dynastic conflicts between the Houses of Hanover and Stuart had given way to a mass movement for political reform. The radicals of the 1790s and 1830s built upon the foundations laid by earlier campaigners—most notably by John Wilkes, the self-styled “Champion of Liberty”—while articulating a new language of Paineite universalism and, increasingly, of working-class consciousness.

The documents and pamphlets preserved in Radicalism and Popular Protest in Georgian Britain, c. 1714–1832, make it possible to trace this transformation, from the street politics of the early Georgian era to the organised reform campaigns of the nineteenth century. Together, these materials illuminate how Britons of the Georgian period reimagined the nation’s future and, in doing so, forged a distinctive and enduring mode of political reformism.

[1] See "radical, adj." in Samuel Johnson, A Dictionary of the English Language (1755), available at https://johnsonsdictionaryonline.com/1773/radical_adj [accessed 12 September 2025]. For an example of a medical application of the word see Anon., The Potable Balsome of Life . . . A Radical and Cordial Balsamick Liquor (London, 1675).

[2] For the constitutional myths that informed popular radicalism in the later eighteenth- and early-nineteenth century see J. Epstein, “The Constitutional Idiom: Radical Reasoning and Action in Early Nineteenth Century England,” Journal of Social History 23 (1990): 553–74.

[3] See R. B. Shoemaker, The London Mob: Violence and Disorder in Eighteenth-Century London (London: Hambledon & London, 2004).

[4] London Magazine or Gentleman’s Monthly Intelligencer 37 (London, June 1768), 329, cited in James L. Fitts, “Newcastle's Mob”, Albion 5, no 1 (1973): 41–49.

[5] This was Queene’s Day—the anniversary of the accession of Queen Elizabeth I, when it was traditional to burn effigies of the Devil.

[6] Fitts, “Newcastle's Mob”, 46.

[7] British Online Archives (hereafter, BOA), Radicalism and Popular Protest in Georgian Britain, c. 1714–1832, “SP 35/16/133: Letter from Thomas Hartopp Regarding Jacobite Sympathies”, 20 June, 1719, available at https://britishonlinearchives.com/documents/59994/sp-3516133-letter-from-thomas-hartopp-regarding-jacobite-sympathies#?xywh=-897%2C0%2C7382%2C3994&cv=1, image 2.

[8] SP 35/21, f. 227, Hartopp, Attorney General, 11 June, 1720.

[9] BOA, “SP 36/83/1/31: Letter from Edward Blacket with the Deposition of James Usher Enclosed”, 11 April, 1746, available at https://britishonlinearchives.com/documents/59543/sp-3683131-letter-from-edward-blacket-with-the-deposition-of-james-usher-enclosed#?xywh=-1946%2C-1%2C8507%2C3692&cv=2, image 3.

[10] BOA, “SP 36/83/2/9: Letter from the Mayor of Newcastle with Correspondence and an Affidavit Enclosed”, 11 April, 1746, available at https://britishonlinearchives.com/documents/59544/sp-368329-letter-from-the-mayor-of-newcastle-with-correspondence-and-an-affidavit-enclosed#?xywh=-1055%2C-1%2C6481%2C2813&cv=4, image 5.

[11] Ibid., available at https://britishonlinearchives.com/documents/59544/sp-368329-letter-from-the-mayor-of-newcastle-with-correspondence-and-an-affidavit-enclosed#?xywh=-2133%2C-1%2C8965%2C3891&cv=6, image 7. The Battle of Sherrifmuir (1715) was a key conflict during the Jacobite rising of the same year in which the Earl of Mar claimed to have held the field.

[12] W. A. Speck, The Butcher: The Duke of Cumberland and the Suppression of the ’45 (Oxford: Blackwell, 1981).

[13] P. D. G. Thomas, British Politics and the Stamp Act Crisis: The First Phase of the American Revolution, 1763–1767 (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1975).

[14] Arthur H. Cash, John Wilkes: The Scandalous Father of Civil Liberty (New Haven, Yale, 2006), xiii.

[15] See North Briton no. 45, available at https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=uc1.31970008271303&seq=339&q1=No+XLVI. Also available at BOA, “D55: The North Briton, XLVI, Vol. II”, available at https://britishonlinearchives.com/documents/58422/d55-the-north-briton-xlvi-vol-ii#?xywh=-1431%2C-1%2C7857%2C4252&cv=250, images 251–273.

[16] BOA, “SP 37/2/33: Charles Yorke and Fletcher Norton's Report on The North Briton No. 45”, 27 April, 1763, available at https://britishonlinearchives.com/documents/60126/sp-37233-charles-yorke-and-fletcher-nortons-report-on-the-north-briton-no-45#?xywh=-1032%2C0%2C6894%2C3730&cv=2, image 3.

[17] BOA, “SP 37/2/34: Deposition of Richard Balfe”, 29 April, 1763, available at https://britishonlinearchives.com/documents/60127/sp-37234-deposition-of-richard-balfe#?xywh=-2599%2C-204%2C7502%2C4060.

[18] His success in Middlesex followed a failed election campaign in the City of London during the same year.

[19] Cash, 210–214; TNA, SP 37/6, f. 191, Information of Nicholas Coga, taken before Sir John Fielding, 30 March, 1768.

[20] Gentleman’s Magazine vol. 38 (1768), 323–35.

[21] Relevant sources in the collection include: BOA, “T 1/468/265-273: Proceedings on the Late Riot at the King's Bench Prison”, 10 May, 1768, available at https://britishonlinearchives.com/documents/59608/t-1468265-273-proceedings-on-the-late-riot-at-the-kings-bench-prison#?xywh=-3460%2C-310%2C11425%2C6183; BOA, “T 1/468/387-388: The London Gazette, No. 10832”, 10 May, 1768, available at https://britishonlinearchives.com/documents/59609/t-1468387-388-the-london-gazette-no-10832#?xywh=-2943%2C-240%2C8843%2C4785.

[22] The most recent biography is Robin Eagles’ Champion of English Freedom: The Life of John Wilkes, MP and Lord Mayor of London (Amberley: Stroud, 2024). See also “Wilkes, John (1725–97)” in L. Namier and J. Brooke, ed. The History of Parliament: the House of Commons 1754–1790 (London: Her Majesty’s Stationery Office, 1964) available at https://www.historyofparliamentonline.org/volume/1754-1790/member/wilkes-john-1725-97.

[23] John Brewer, Party Ideology and Popular Politics at the Accession of George III (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1976) 184–86.

[24] J. Cozens, “The Temple Bar Token: A Portal to London’s Radical Past”, in Tokens of Love, Loss and Disrespect, 1700–1850, ed. Sarah Lloyd and Timothy Millett (London: Paul Holberton, 2022), 143–49.

[25] George Rudé, “Wilkes Radical essay”, 159.

[26] William Purdie Treloar, Wilkes and the City (London: J. Murray, 1917), 209. His declining interest in radical politics is particularly notable after his appointment as City Chamberlain in 1779.

[27] TNA, TS 24/3/34, LCS, Handbill Advertising a Petition (April 1793).

[28] Though, as Malcolm Crook points out, the 1793 Constitution was never implemented in France and in practice voting rights for men were linked to the payment of some form of direct taxation. See Malcolm Crook, How the French Learned to Vote: A History of Electoral Practice in France (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2021), especially chapter one, “One Man, One Vote: The Long March towards Universal Male Suffrage”, 16–41.

[29] TNA, TS 24/3/9, LCS, Reformers Not Rioters, (London, 1794), 5.

[30] For an example of a report on LCS tavern debates see BOA, “HO 42/37/227: Debate on the Principles and Conduct of Charles James Fox”, 3 November, 1795, available at https://britishonlinearchives.com/documents/59036/ho-4237227-debate-on-the-principles-and-conduct-of-charles-james-fox. For details on the use of spies see Clive Emsley, “The Home Office and Its Sources of Information and Investigation 1791–1801”, The English Historical Review 94, no. 372 (1979): 532–561.

[31] These were Thomas Muir, Thomas Fyshe Palmer, Maurice Margarot, and Joseph Gerald. For details of Muir’s trial see BOA, “D31: The Trial of Thomas Muir, Esq.”, 1793, available at https://britishonlinearchives.com/documents/58328/d31-the-trial-of-thomas-muir-esq.

[32] Spies’ testimonies, including those of George Lynam and John Goves, were called upon at the treason trials against the LCS see State Trials, vol. 24, 805–7, 1144. BOA’s Radicalism and Popular Protest in Georgian Britain, c. 1714–1832, contains examinations of suspects by the Privy Council and the shorthand writers’ notes on the trial at the Old Bailey. See BOA, “PC 1/21/35A: Papers Relating to the London Corresponding Society”, available at https://britishonlinearchives.com/documents/60304/pc-12135a-papers-relating-to-the-london-corresponding-society; BOA, “TS 11/993/3705: Papers Relating to the King v Thomas Hardy and Other Members of the London Corresponding Society, Part 1”, available at https://britishonlinearchives.com/documents/60396/73839-b1588; BOA, "TS 11/994: Papers Relating to the King v Thomas Hardy and Other Members of the London Corresponding Society, Part 2”, available at https://britishonlinearchives.com/documents/60397/73839-b1589. See also BOA, “D31: The Trial at Large of John Horne Tooke, Esq., for High Treason”, 1794, available at https://britishonlinearchives.com/documents/58326/d31-the-trial-at-large-of-john-horne-tooke-esq-for-high-treason.

[33] E. P. Thompson, “Hunting the Jacobin Fox”, Past & Present 142 (1994): 94–140.

[34] A. V. Coats and P. MacDougall, ed. The Naval Mutinies of 1797: Unity and Perseverance (Woodbridge: Boydell Press, 2011); R. Wells, Insurrection: The British Experience, 1795–1803 (Gloucester: Allen Sutton, 1986); M. Elliott, Partners in Revolution: The United Irishmen and France (London: Yale University Press, 1982); Thomas Pakenham, The Year of Liberty (London: Hodder and Stoughton, 1969).

[35] Samuel Bamford, Early Days, 58.

[36] Bamford, Passages in the Life of a Radical, 150.

[37] Ibid., 150.

[38] Poole, Peterloo, 350.

[39] See BOA, “D34: The Trial of Henry Hunt, Esq., for an Alleged Conspiracy to Overturn the Government”, 1820, available at https://britishonlinearchives.com/documents/58338/d34-the-trial-of-henry-hunt-esq-for-an-alleged-conspiracy-to-overturn-the-government.

[40] See chapter 12 of Steve Poole and Nicholas Rogers, Bristol from Below: Law, Authority and Protest in a Georgian City (Martlesham: Boydell Press, 2017).

[41] For a succinct overview, see the table in Philip Salmon & Kathryn Rix, “Who Should Have the Vote? What electoral rights did Britons have in the century before 1918?”, History Today 68, no. 8 (2018): 24–35.

[42] See Malcolm Chase, Chartism: A New History (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2007); Malcolm Chase, “What Did Chartism Petition For? Mass Petitions in the British Movement for Democracy”, Social Science History 43, no. 3 (2019) 531–551.

© Crown Copyright

Text reproduced by permission of The National Archives, UK [2025].