The media, in its many forms, has played a key role in transforming British royal weddings into the huge national and global events that they are today. Before the marriage of Queen Victoria to Prince Albert on 10 February 1840, royal marriages were typically conducted at night, keeping the event relatively private. Albert and Victoria, however, decided instead to marry in the early afternoon, which allowed crowds of well-wishers to gather on the streets in celebration.[1] This decision can be seen as catalysing the increasing size and visibility of British royal weddings.

British Online Archives, The Illustrated London News, 1842–2003, “May 1911, The Reign of Queen Victoria Record Number”, image 9.

British Online Archives, The Illustrated London News, 1842–2003, “May 1911, The Reign of Queen Victoria Record Number”, image 9.

The Illustrated London News (ILN), one of the earliest and most successful weekly illustrated newspapers in Britain, was a key player in reporting on royal weddings. Throughout its 161 year run, the paper remained committed to covering the marriages of royalty around the world, paying particular attention to British royal weddings. What began as articles on royal weddings soon evolved into special marriage supplements, which, in turn, evolved into entire so-called “Wedding Numbers”.

This article will explore the ILN’s coverage of British royal weddings, from the marriage of Prince Albert Edward (later King Edward VII) to Alexandra of Denmark in 1863, to that of Prince Charles (now King Charles III) to Diana Spencer in 1981. As a fervent supporter of the monarchy, the ILN often used its wedding reporting to promote the British monarchy, propagating its image as the pinnacle of British identity. This image was connected intrinsically to traditional interpretations of gender and the British class system. The ILN also worked to consolidate the royal wedding as a site of national unity by advertising and commemorating such events, thereby encouraging the public to participate in celebration, both physically and cognitively. As the following discussion will demonstrate, this agenda aimed to strengthen the monarchy’s role in society, by presenting royals as figures that the public should imitate and unite around.

British Online Archives, The Illustrated London News, 1842–2003, “14 March 1863”, image 23.

British Online Archives, The Illustrated London News, 1842–2003, “14 March 1863”, image 23.

The first marriage of a British heir that was covered by the ILN was that of Prince Albert Edward to Alexandra of Denmark, which took place on 10 March 1863. The paper covered the wedding in detail, publishing an article advertising the event on 7 March 1863, a dedicated marriage supplement on 14 March 1863, and various illustrations and articles about the wedding throughout the following month.[2] The article that appeared on 7 March was titled “Tuesday, The Tenth of March” and was featured on the front page of the edition. It is a particularly strong example of the ILN’s role in promoting the royal wedding. Both the plainness of the title and its position on the front page worked to ensure that the date of the wedding was known widely, building excitement and implicitly encouraging participation on the day.

British Online Archives, The Illustrated London News, 1842–2003, “7 March 1863”, image 1.

British Online Archives, The Illustrated London News, 1842–2003, “7 March 1863”, image 1.

By updating its readers with frequent, detailed reports, the ILN aimed to make the public invested in the royal marriage. Based on the reporting within the special supplement, it is apparent that this worked. It is said that “thousands of persons” lined the streets to witness the wedding procession, and that the crowd was “a densely-packed mass such as had never before been seen”.[3] Around St. Paul’s Churchyard, people even gathered on rooftops, reportedly in as high a concentration as on the roads.[4]

While the ILN certainly played a role in advertising the wedding, and paid much attention to it themselves, the turnout was greater than even they anticipated.[5] This is perhaps unsurprising, as no royal wedding prior to this had caused such scenes. The ILN did, however, offer an explanation for their oversight, by claiming that the desire to witness and celebrate the royal wedding was deeply natural and “universal”, going so far as to suggest that those who did not participate “were suffering from that irritable disorder”.[6] It also drew on the recent death of Prince Albert as an explanation for the massive display, proposing that the crowds had gathered not only to celebrate the wedding, but to display their “sympathy and affection” for the mourning Queen Victoria.[7] Together, these explanations suggest that there was an innate sense of national unity created around the Crown on this day, because it was experiencing two major life events: marriage and death. Being such major life events, these were occasions that much of the public had personal experience with. As such, it was easy for many to empathise with, and partake in, the strong emotions that surrounded the wedding, which, in-turn, helped to consolidate the narrative that the response was natural and “universal”.

British Online Archives, The Illustrated London News, 1842–2003, “29 November 1947”, image 1.

British Online Archives, The Illustrated London News, 1842–2003, “29 November 1947”, image 1.

The idea of the royal wedding as a site of national unity was conspicuous in the media during the wedding of Princess Elizabeth (later Queen Elizabeth II) to Prince Philip, which took place on 20 November 1947. In the aftermath of the Second World War, with Britain not yet fully recovered from its devastating effects, the wedding became a national focal point, providing, according to Winston Churchill, a “splash of colour” in the otherwise difficult conditions of post-war austerity and imperial decline.[8]

According to the ILN, in its dedicated edition on this royal wedding, the amount of people who gathered to celebrate the event in London was “greater than that on previous State occasions”, despite the fact that, “in keeping with post-war austerity, the decorations and arrangements could not compare with previous occasions”.[9] Aside from this, there are few direct references to the difficulties that Britain faced during the post-war period, though this is largely to be expected in a wedding edition, with its focus on celebration. The ILN instead preferred to focus on the “obvious happiness” of the royal couple and the “love and respect” which was given by the crowds to the newlyweds.[10] This light, happy tone continued throughout the number, portraying the royal wedding as a universally joyful event, and presenting Britain as unified through celebration.

British Online Archives, The Illustrated London News, 1842–2003, “29 November 1947”, image 3.

British Online Archives, The Illustrated London News, 1842–2003, “29 November 1947”, image 3.

The reportedly overwhelmingly positive response from the public to Elizabeth’s and Philip’s wedding was again presented by the ILN as natural. In its coverage of this wedding, the ILN claimed that public celebration was not “irrational or merely sentimental”, but an “automatic response of the heart”.[11] In arguing this, however, the ILN implied that people did, in fact, believe that these large-scale celebrations were “irrational or merely sentimental”, which would suggest that the urge to “rejoice” at the royal marriage was not the universal response that the paper painted it to be.[12] Regardless, as an avid supporter of the monarchy, the ILN pushed this narrative so as to portray the royal wedding, and therefore the royal family, as the centre of national unity. Furthermore, by framing positive reactions as “automatic” and “universal”, the ILN implied that these reactions were instinctual, thus framing the monarchy as a natural part of British society. This narrative aimed to consolidate the social influence of the British Crown by presenting it not as a socially constructed power hierarchy, but as an inherent, innate part of human life, which people are naturally drawn to unite around.

The ILN aimed to consolidate the monarchy’s social influence further by using the royal wedding to construct and communicate an idealised image of national identity to the public through its presentation of the royals. This idea worked closely with that of promoting national unity by presenting the royals as epitomising British identity. As is apparent from the reporting in the 1947 wedding edition, royal weddings had become firmly cemented as public events in the decades after the huge turnout at Prince Albert Edward’s and Alexandra of Denmark’s wedding. Consequently, they became excellent places in which an idealised version of British national identity could be promoted by the media.

British Online Archives, The Illustrated London News, 1842–2003, “28 April 1923”, image 1.

British Online Archives, The Illustrated London News, 1842–2003, “28 April 1923”, image 1.

The ILN’s coverage of the marriage of Prince Albert of York (later King George VI) to Elizabeth Bowes-Lyon in 1923 showcases the ways in which the media constructed the royal model of British identity. Despite most people expecting that Albert, as second in line to the throne, would not become king, and despite Elizabeth not being of royal birth (a significant break in tradition), the wedding received ample attention from the ILN, including a dedicated “Wedding Number”.[13]

The approach that the ILN took to constructing this couple as idealised models of British identity is noticeably gendered, and is tied-up closely with concepts of modernity and class. In its “Wedding Number”, the ILN supplied its readers with biographies of Albert and Elizabeth. Yet despite being much more well-known to the public than Elizabeth, Albert received significantly more personal attention in his biography—which spotlighted his “charming personality” and praised his social work and “good sportsmanship”—than she did.[14] In contrast, Elizabeth was presented primarily in the context of her heritage and ancestry, with about half of her biography page detailing her family’s historical connections to Scottish nobility and her childhood home: Glamis Castle.[15] This is not to say that there were no details given regarding Elizabeth’s character. For example, the ILN reported that, as a child, she was “always sedate and restrained”, and that, as an adult, she “has grown into charming womanhood”.[16]

British Online Archives, The Illustrated London News, 1842–2003, “28 April 1923”, images 20 and 27.

British Online Archives, The Illustrated London News, 1842–2003, “28 April 1923”, images 20 and 27.

While differing in quantity, the insights into Albert’s and Elizabeth’s personalities offered by the ILN are deeply gendered, relying on traditional ideas to construct idealised masculine and feminine identities. The concept of modernity also interacted with that of gender here. For example, Albert was praised for breaking tradition by taking on “the free-and-easy manner” of his fellow students while at university. Elizabeth, on the other hand, was praised for having “escaped the handicaps of the ultra-modern spirit” and retaining “that exquisite simplicity and charm of manner which has become something of a lost art”.[17] These comments, alongside those on the couple’s personalities, suggest that it was commendable, in the view of a publication such as the ILN, for men to embrace modern values, but that this was not the case with regard to women. The ILN framed traditional attributes of femininity, such as humility and “charm”, as unique characteristics that defined Elizabeth, rendering her an appropriate bride for Albert and therefore a natural royal. Though the ILN claimed these attributes to be “a lost art” in terms of the wider population, this framing of Elizabeth’s personality aimed to portray the ideal feminine identity as one which adhered to tradition. Inversely, the paper praised Albert for embodying the ideal masculine identity as one which, it would seem, was less restricted by tradition.

The heavy focus on Elizabeth’s distant royal heritage also reveals the strong role that class played in the ILN’s construction of the royal-to-be as an optimal representative of British identity. When the fiancé of a royal was not born into royalty themselves, the ILN felt compelled to justify their suitability for the role by explaining their familial connections to the upper-class. This was such a pervasive angle that it remained obvious 58 years later, within the coverage of Prince Charles’ and Diana Spencer’s wedding in 1981. There are striking similarities between the ILN’s reporting on Elizabeth and Diana, not least the way in which attention was drawn to the fact that Diana was a “descendent of an ancient line” and member of a family that “has for centuries [. . .] been closely linked to royalty”.[18] The ILN likewise noted that Diana was “born on a royal estate”, echoing its focus in 1923 on Glamis Castle as Elizabeth’s childhood home.[19]

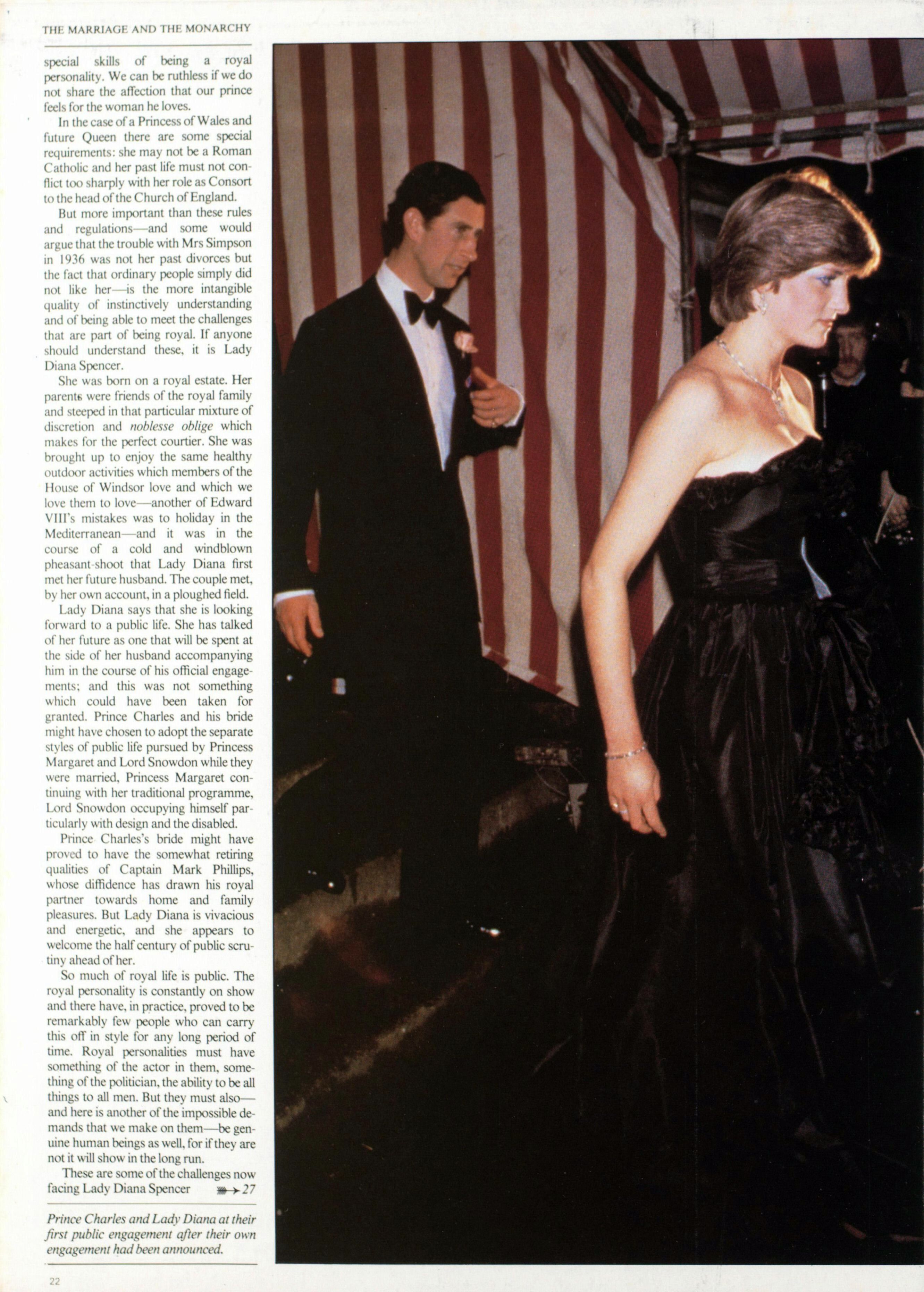

British Online Archives, The Illustrated London News, 1842–2003, “July 1981, Royal Wedding Special Number”, image 20.

British Online Archives, The Illustrated London News, 1842–2003, “July 1981, Royal Wedding Special Number”, image 20.

Given the historical status of royalty as the highest social class, it is perhaps unsurprising that the ILN felt that it had to justify the acceptance of a non-royal into the royal family. However, this insistence upon social status also reflected the importance of the class system within British society and the overarching concept of national identity. While both Elizabeth’s and Diana’s marriages into the royal family were presented as welcome breaks from tradition, the ILN was nevertheless eager to highlight how both women were members of the nobility. Thus, from 1923 to 1981, the implication remained: the embodiment of the ideal British identity could not be epitomised by those hailing from lower social classes. Publications such as the ILN therefore helped to ingrain the class system into British national identity.

Yet not all British royals-to-be embodied the principles deemed necessary to represent the ideal national identity, as the engagement of King Edward VIII to Wallis Simpson would prove. The ensuing scandal was predicated upon Wallis’s status as an American twice-divorcée and ultimately led to the abdication of King Edward VIII in December 1936. 45 years later, in Prince Charles’ and Diana Spencer’s “Wedding Number”, the ILN reflected upon the controversy of Edward’s and Wallis’ marriage, stating that “ordinary people simply did not like her”.[20] Yet until 2002, the Church of England did not allow a divorcée with a living ex-spouse to remarry, which caused a constitutional crisis between the Anglican Church and the Crown.[21] Ultimately, this conflict was at the root of the scandal, but, as the ILN later alluded to, Wallis’ image did cause significant “trouble” with the public, as her American nationality and past marriages were out of line with the image of royalty that the media, and especially the ILN, had crafted through reporting upon previous royal fiancés, such as Elizabeth Bowes-Lyon.[22]

The ILN, however, was incredibly careful when it reported upon the engagement of Edward and Wallis, conspicuously avoiding critiquing Edward in its reporting on the crisis and his abdication (upon which he was made Duke of Windsor).[23] The paper, somewhat surprisingly, also took care not to criticise Wallis too harshly. Although it labelled her “the cause of the constitutional crisis”, it also chose to highlight her desire to “avoid any action or proposal which would hurt or damage his Majesty or the Throne”.[24] As a publication that avidly supported the monarchy, the ILN evidently did not want to portray the Crown negatively, whether wider society deemed the actions of the royals acceptable or not. The ILN’s tendency to construct royalty as pinnacles of national identity also meant that it could not criticise members of the royal family without threatening this ideological construct, thereby diminishing the paper’s own efforts to consolidate the Crown’s social influence. Consequently, the ILN avoided ascribing blame to Edward or his fiancé, despite the scandal that their engagement had caused.

British Online Archives, The Illustrated London News, 1842–2003, “12 June 1937”, image 22.

British Online Archives, The Illustrated London News, 1842–2003, “12 June 1937”, image 22.

The ILN’s coverage of the marriage of Edward and Wallis was equally cautious. The paper chose to publish the couple’s “Wedding-Day Portrait” on 12 June 1937 with a straightforward caption on a page titled “The Camera as Recorder: Pictorial News at Home and Abroad”.[25] This small report is, clearly, an outlier in the ILN’s reporting on British royal weddings, published tactfully to ensure that it neither snubbed nor celebrated the duke’s marriage to the perceived “cause of the constitutional crisis”.[26] Again, this approach was rooted in the idea of the royals as symbols of national identity and pillars of the British class system. Even upon his abdication, the duke remained at the top of the social hierarchy. Thus, avoiding coverage of his wedding could have been interpreted as an insult to the Crown on the part the ILN, which throughout its existence had positioned itself as a firm supporter of the monarchy. However, because Wallis, as an American divorcée, did not epitomise British identity, and because the duke’s decision to abdicate in order to marry her was equally out of line with this ideological construct, the ILN could not publicise the wedding without inadvertently promoting a configuration of national identity that was out of line with the Crown’s public image. Even if they wanted to cover the wedding through a dedicated supplement or number, the impact of the scandal was so great that the couple married privately in France. Consequently, the event was unable to garner the public participation that featured so centrally in other wedding reports.[27] The wedding, therefore, did not radiate the idealised image of British national identity that the ILN sought to promote, neither could it be utilised as a site of national unity, and, as such, it was reported upon minimally and objectively.

The ILN’s coverage of British royal weddings was extensive and the paper maintained a surprisingly consistent approach to the topic over its long run. The pursuit of British national unity and identity remained core agendas in the ILN’s wedding reporting, created and pushed largely to consolidate the monarchy’s social influence. The foregoing discussion has demonstrated how these agendas utilised and reflected broader notions of gender and class, often in remarkably similar ways across time. Today, these concepts still influence the ways in which the media presents British royals, using tactics that both resemble and differ from the reporting of the ILN. For example, Kate Middleton was celebrated for becoming the “first middle class queen-in-waiting” when she married Prince William in 2011, a notable departure from the narrative pushed by the ILN during its lifespan, which posited that high social status was a natural, and indeed, necessary characteristic of a royal-to-be. [28] In contrast, Meghan Markle’s nationality, class, occupation, and, most significantly, race, have garnered her mixed and, increasingly, negative attention from the media since her marriage to Prince Harry in 2018, showcasing the power that traditional, British interpretations of identity markers still have in terms of defining the distinctive image of national identity that has been constructed around and through the royals.[29] These identity markers continue to influence media commentary on members of the royal family, not least because of the perception of the Crown as the epitome of British national identity and as a powerful source of national unity—ideas which, as this discussion has demonstrated, the ILN played a key role in creating and propagating throughout its run.

You can explore the ILN’s extensive back catalogue on BOA’s innovative digital archive. Visit the collection page for The Illustrated London News, 1842–2003, to learn more. The back catalogues of the ILN’s nine so-called "sister” titles are also available to explore via BOA.

[1] “The Marriage of Queen Victoria & Prince Albert”, London Museum, available at https://www.londonmuseum.org.uk/collections/london-stories/marriage-queen-victoria-prince-albert/.

[2] “Tuesday, The Tenth of March”, The Illustrated London News, 7 March 1863, available via BOA at https://britishonlinearchives.com/documents/51520/17-march-1863#?xywh=-284%2C1103%2C3163%2C1562&cv=, images 1–2; “Marriage Supplement to The Illustrated London News”, The Illustrated London News, 14 March 1863, available via BOA at https://britishonlinearchives.com/documents/51521/14-march-1863#?xywh=-1143%2C-6%2C8570%2C4637&cv=16, images 17–30; The Illustrated London News, 4 April 1863, available via BOA at https://britishonlinearchives.com/documents/51524/4-april-1863#?xywh=-1466%2C0%2C9479%2C4682&cv=15, image 16; The Illustrated London News, 25 April 1963, available via BOA at https://britishonlinearchives.com/documents/51527/25-april-1863#?#%23h=marriage&cv=&xywh=-140%2C0%2C3459%2C4698, images 1 and 18.

[3] “Marriage Supplement to The Illustrated London News”, The Illustrated London News, 14 March 1863, available via BOA at https://britishonlinearchives.com/documents/51521/14-march-1863#?xywh=-1117%2C0%2C8570%2C4637&cv=16, images 17 and 21.

[4] Ibid., image 21.

[5] “Royal Wedding Special Number", The Illustrated London News, July 1981, available via BOA at https://britishonlinearchives.com/documents/57397/july-1981-royal-wedding-special-number#?xywh=0%2C-820%2C8385%2C5348&cv=57, image 58.

[6] “Marriage Supplement to The Illustrated London News”, The Illustrated London News, 14 March 1863, available via BOA at https://britishonlinearchives.com/documents/51521/14-march-1863#?xywh=-435%2C0%2C7325%2C4672&cv=17, image 18.

[7] Ibid.

[8] See Edward Owens, The Family Firm: Monarchy, Mass Media and the British Public, 1932–53 (University of London Press), especially chapter five, available at https://read.uolpress.co.uk/read/the-family-firm/section/a564e830-4ce5-4c2d-917b-3083c35af79e.

[9] The Illustrated London News, 29 November 1947, available via BOA at https://britishonlinearchives.com/documents/56033/29-november-1947#?xywh=-2292%2C-246%2C7707%2C4915, image 13.

[10] Ibid., image 3.

[11] Ibid., image 4.

[12] Ibid.

[13] “Wedding Number”, The Illustrated London News, 28 April 1923, available via BOA at https://britishonlinearchives.com/documents/54724/28-april-1923#?xywh=-3081%2C-1%2C9239%2C4564&cv=.

[14] “H.R.H. The Duke of York”, The Illustrated London News, 28 April 1923, available via BOA at https://britishonlinearchives.com/documents/54724/28-april-1923#?xywh=-484%2C0%2C6978%2C4450&cv=19, image 20.

[15] “Lady Elizabeth Bowes-Lyon”, The Illustrated London News, 28 April 1923, available via BOA at https://britishonlinearchives.com/documents/54724/28-april-1923#?xywh=-499%2C-1%2C6836%2C4360&cv=26, image 27.

[16] “Wedding Number”, The Illustrated London News, 28 April 1923, available via BOA at https://britishonlinearchives.com/documents/54724/28-april-1923#?xywh=-3081%2C-1%2C9239%2C4564&cv=, images 11 and 27.

[17] Ibid., images 20 and 27.

[18] “Royal Wedding Special Number”, The Illustrated London News, July 1981, available via BOA at https://britishonlinearchives.com/documents/57397/july-1981-royal-wedding-special-number#?xywh=-2410%2C-208%2C7674%2C4153, images 17 and 38.

[19] Ibid.

[20] Robert Lacey, “The Marriage and the Monarchy”, The Illustrated London News, July 1981, available via BOA at https://britishonlinearchives.com/documents/57397/july-1981-royal-wedding-special-number#?xywh=-242%2C0%2C5856%2C3735&cv=19, image 20.

[21] “Marriage after divorce”, The Church of England, available at https://www.churchofengland.org/life-events/your-church-wedding/just-engaged/marriage-after-divorce.

[22] Lacey, “The Marriage and the Monarchy”, available via BOA at https://britishonlinearchives.com/documents/57397/july-1981-royal-wedding-special-number#?xywh=-242%2C0%2C5856%2C3735&cv=19, image 20.

[23] The Illustrated London News, 12 December 1936, available via BOA at https://britishonlinearchives.com/documents/55450/12-december-1936#?xywh=-986%2C0%2C8112%2C4389&cv=8, images 9–24; “Accession Number”, The Illustrated London News, 19 December 1936, available via BOA at https://britishonlinearchives.com/documents/55451/19-december-1936#?xywh=-379%2C-1%2C6836%2C4360&cv=21, images 23–46.

[24] “The Cause of the Constitutional Crisis: Mrs. Ernest A. Simpson”, The Illustrated London News, 12 December 1936, available via BOA at https://britishonlinearchives.com/documents/55450/12-december-1936#?xywh=-375%2C0%2C6880%2C4387&cv=16, image 17.

[25] “The Camera as Recorder: Pictorial News at Home and Abroad”, The Illustrated London News, 12 June 1937, available via BOA at https://britishonlinearchives.com/documents/55477/12-june-1937#?xywh=-437%2C-1%2C6836%2C4360&cv=21, image 22.

[26] “The Cause of the Constitutional Crisis: Mrs. Ernest A. Simpson”, available via BOA at https://britishonlinearchives.com/documents/55450/12-december-1936#?xywh=-375%2C0%2C6880%2C4387&cv=16, image 17.

[27] “The Camera as Recorder: Pictorial News at Home and Abroad”, available via BOA at https://britishonlinearchives.com/documents/55477/12-june-1937#?xywh=-437%2C-1%2C6836%2C4360&cv=21, image 22.

[28] Gordon Rayner, “Royal wedding: Kate Middleton will be first middle class queen-in-waiting”, The Telegraph, 16 November 2010, available athttps://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/uknews/theroyalfamily/8137234/Royal-wedding-Kate-Middleton-will-be-first-middle-class-queen-in-waiting.html; Tim Adams, “Royal engagement: Kate’s triumph for Britain’s middle classes”, The Guardian, 21 November 2010, available at https://www.theguardian.com/uk/2010/nov/21/prince-william-kate-middleton-engagement.

[29] For examples, see Micheline Maynard, “Meghan Markle: Six reasons why she divides people – even Americans”, ABC News, 17 May 2018, available at https://www.abc.net.au/news/2018-05-17/meghan-markle-american-tv-actresses-prince-harry-windsor-castle/9766742; Ed Holt, “Prince Harry and Meghan Markle’s long list of royal wedding BLUNDERS from ‘tiara-gate’ to the divorcee’s ‘too white’ wedding dress”, MailOnline, 5 July 2025, available at https://www.dailymail.co.uk/news/royals/article-14863637/prince-harry-meghan-markle-royal-wedding-blunders.html.