The Illustrated London News, 1842–2003

Over 150 years of influential illustrated news

The publication of the first issue of the Illustrated London News on 14 May 1842 marked a revolution in the gathering and representation of news through its pioneering use of pictorial reportage.“Pageantry or Propaganda? The Illustrated London News and Royal Visitors in Ireland," Irish Arts Review Yearbook 16 (2000): 86–93.

Access the full collection

Access the full archive of The Illustrated London News, 1842–2003.

Institutional Free Trial

Start your free trialRegister for a free 30-day trial of The Illustrated London News, 1842–2003, for your institution.

Institutional Sales

Visit Sales PagesellFor more information on institutional access, visit our sales page.

Already have a license? Sign in.

Explore one of the most eye-catching and pioneering ventures in British print media.

Containing over 250,000 images, this fascinating and visually stunning collection brings together the extensive back catalogue of one of the most influential and successful publications in the history of British print media: The Illustrated London News (ILN), founded in 1842 by Herbert Ingram. Whilst working as a newsagent and printer two consumer trends caught his attention: that papers featuring woodcut engraved illustrations tended to sell better and that people frequently requested “London news”, as opposed to a specific publication. Developments in printing technology, such as faster rotary presses, helped Ingram translate his vision of “illustrated news” into a reality.

This vision proved timely and lucrative. The first edition of the ILN, which appeared on 14 May 1842, sold 26,000 copies. It cost sixpence, featured 32 illustrations, and reported upon the “Great Fire of Hamburg”, as well as the young Queen Victoria’s first “Masquerade Ball”. In fact, celebration of the British monarchy emerged as a popular theme throughout the paper’s content. By 1855, 130,000 copies were being sold weekly, a figure that had more than doubled by the early 1860s. The paper targeted a broadly middle class readership, with Ingram’s embrace of liberalism ensuring that it backed reformist agendas, such as the plight of industrial workers and the need for better public amenities and urban infrastructure. Yet because Ingram embodied the Victorian ideal of the “self-made man”, the ILN was equally capable of sympathising with big business. It likewise espoused Britain’s imperial project.

Due to its phenomenal success, the ILN eventually faced serious competition from The Graphic, founded in 1869 by William Luson Thomas, who had honed his skills as an engraver for the ILN. During the twentieth century, the ILN shed much of its early visual style as it embraced photography. Over time, it acquired a number of its rival publications, including The Graphic, and launched several successful papers of its own, such as The Illustrated War News.

Excitingly, the extensive back catalogues of the ILN and its nine so-called “sister” titles are available to explore on BOA’s digital archive. These impressive resources enable students, researchers, and educators to investigate the history of modern Britain, and especially the history of British print journalism, in remarkable detail. Perhaps most importantly, the ILN and its related publications facilitate examination of an almost endless variety of historical events, concepts, and trends—British and otherwise.

Contents

Highlights

Licensed to access 15 December 1849—Condition of Ireland

Between 1845 and 1852, Ireland’s population experienced starvation, disease, poverty, and mass emigration as a result of widespread potato blight. Published in December 1849, this article (image 9) captured the devastating consequences of the “Great Famine”. The depiction of a ghost village is a powerful reminder of the countless evictions that occurred across the island, as people struggled to pay rents and landlords sought to reduce their financial burdens.

Licensed to access 6 March 1852—The Great Exhibition

Organised by Prince Albert, and staged in the Crystal Palace—which was purpose-built for the occasion—the Great Exhibition of 1851 showcased Britain’s industrial capacity and imperial reach. The ILN was instrumental in documenting this quintessentially Victorian spectacle for the British public, publishing intricate panoramas of the exhibition that detailed the exotic displays from across the globe. This illustration (image 20) was based on daguerreotypes by Richard Beard. It was the last in the ILN’s series on the exhibition.

Licensed to access 25 April 1896—London Underground and Advertisements

Published in April 1896, this illustration (image 26) spotlighted a key technological innovation on London’s Underground system—the advent of onboard station indicators. Yet the article also captured the associated advancement of consumer culture in Britain—advertisements for well-known brands, such as Bovril and Colman’s, are conspicuous. Driven by rapid industrialisation and the rise of an aspirational middle class, the Victorian era witnessed a significant expansion in commercial advertising.

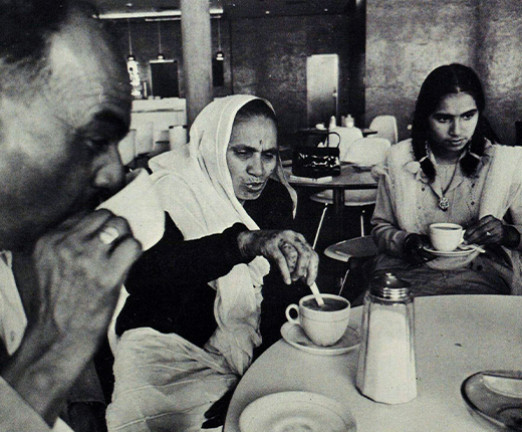

Licensed to access 4 May 1968—Britain Divided

During the 1960s, the ILN frequently reported upon national debates surrounding immigration. Titled “Britain Divided”, this article (image 7), which was published in early May 1968, spotlighted the social polarisation sparked by the Conservative MP, Enoch Powell. He had delivered his controversial “Rivers of Blood” speech in Birmingham a few days previously.

Insights

Disasters and tragedies were a conspicuous feature of the ILN’s coverage. News of the “Great Fire of Hamburg” arrived prior to publication of the first edition. Aware of the commercial rewards to be reaped from the public’s interest in unfortunate events, Ingram and his reporters scrambled to include coverage. Shipwrecks (such as the loss of the SS Princess Alice in 1878) and railway accidents (such as the “Tay Bridge Disaster” of December 1879) were reported upon extensively. So too were natural disasters across the globe, such as the major flooding that occurred in China in 1931.

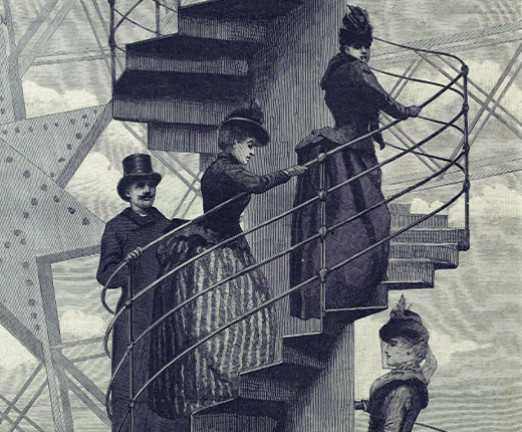

The ILN captured significant cultural trends. It featured critical reviews of music, opera, and the theatre. It also printed literature penned by influential authors, such as Robert Louis Stevenson and Thomas Hardy. Celebrated artwork was often replicated by the paper’s skilled illustrators. Art exhibitions and notable cultural events, such as the Great Exhibition of 1851, received much attention. In later years, the ILN kept readers informed about key events in and around London via weekly entertainment guides.

The ILN pioneered technological innovation. Ingram’s vision of weekly illustrated news was ambitious and demanding, but was rendered feasible by the advent of the steam press and the subsequent arrival of faster rotary presses during the 1840s. In 1860, the paper became the first to publish illustrations produced by photographing straight onto woodblock. Under William Ingram (Herbert’s son), the ILN moved from wood to process engraving. In 1887, the paper printed photographs using the halftone process. The rotary photogravure process was introduced by William’s son, Bruce, who became editor in 1900. This imbued printed photographs with more depth and a smoother tone

It has been remarked that the ILN “done well out of wars” (Robert Hampson, 2009). Coverage of global conflicts was a salient feature of the publication, a trend that was consolidated by the appointment of Dr Charles Mackay, who specialised in foreign affairs, as editor in 1852. The ILN reported upon practically every major conflict throughout the mid to late-nineteenth century, such as the Crimean War (1853–56), the Franco-Prussian War (1870–71), the Afghan War (1878–79), and the First Boer War (1881). During the twentieth century, the ILN likewise paid close attention to major conflicts, such as the world wars, the destabilisation of the Middle East, the “Suez Crisis” of 1956, the Vietnam War (1954–75), and the “Troubles” that broke out in Northern Ireland in 1968.

The ILN celebrated Britain’s imperial reach—news of, and illustrations depicting, far-flung parts of the empire featured constantly. A key strength of this collection is that it allows you to track a large portion of Britain’s imperial history—from the Victorian heyday of the empire, through to its fragmentation during the twentieth century. It is likewise possible to explore the consequent emergence of independence struggles and post-colonial movements, as well as the significant economic, political, and demographic trends that imperial retreat generated within the United Kingdom.

Unlock Historical Research for Your Institution

Provide your students and researchers with direct access to unique primary sources.

Related Media

Key Events in The Illustrated London News: Part One Videos

Key Events in The Illustrated London News: Part Two Videos

Document of the Week: “The Impact of the Immigrants” (1968) Document of the Week

Document of the Week: Tay Bridge Disaster Document of the Week

Defying Expectations: South Asian Women in British Print Media Articles

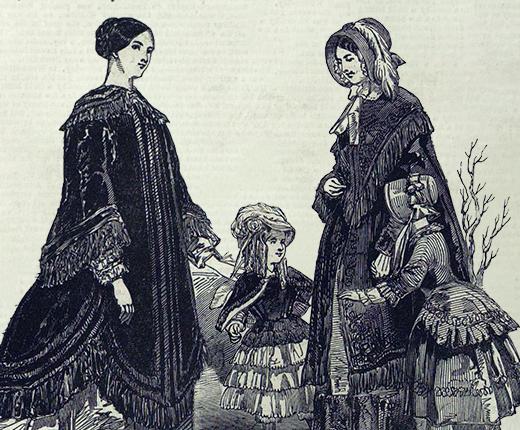

Document of the Week: Winter Fashions Advertisement, The Illustrated London News (1847) Document of the Week

Document of the Week: “Christmas Crackers” (1847) Document of the Week

.svg)