Last week our Editor, Nishah Malik, presented a paper at the Women’s History Network Conference. We’re delighted to share the full paper here in case you missed it.

British Online Archives is home to over six million primary sources grouped within over 150 collections, covering more than five centuries of global history. Among these holdings are several periodicals published throughout the late nineteenth century and twentieth century that shaped British understandings of empire: The Illustrated London News, The Sphere, Britannia and Eve, and The Graphic. These periodicals not only documented political and social events, but also shaped the public imagination of empire. This paper, focusing on three case studies, will look specifically on the representations of South Asian women within these publications.

South Asian women have long fought for equal rights and autonomy, challenging both patriarchal and cultural norms and colonial narratives that have sought to define them. They have struggled with cultural and sexual limitations for generations, not only in South Asia but throughout the diaspora. In the nineteenth and twentieth centuries British press, South Asian women were frequently depicted through a lens of subjugation. Many accounts insinuated that because of their modest dress, known as purdah, they were suppressed and backwards. The term purdah, which translates as “curtain” in Hindi and Urdu, referred to cultural and religious practices of female seclusion in the Indian subcontinent among both Hindus and Muslims. This could take different forms such as the physical separation of women from men in public spaces, the wearing of clothing, often a veil, that concealed the body to maintain modesty. To the Western gaze, however, purdah became a shorthand for oppression, repeatedly criticised as a symbol of women’s lack of freedom and autonomy.

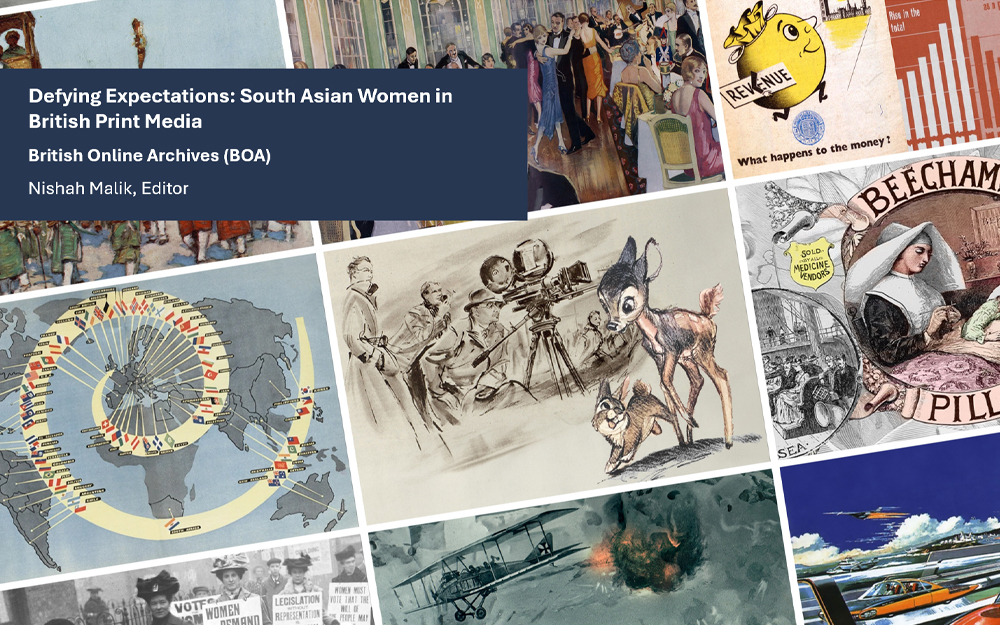

British Online Archives, Britannia, "The Women of India”, 8 February 1929.For example, on 8 February 1929, Britannia published an article titled “The Women of India”. It discussed child marriage, the caste system, and women’s restricted freedoms, ultimately framing Indian women as victims of regressive traditions. In particular, it claimed that “the customs of purdah ail” women and denied them education. The article ultimately frames British authority as essential to women’s emancipation, suggesting that only Britain could “inspire the peoples of that immense country by precept and example”.

British Online Archives, Britannia, "The Women of India”, 8 February 1929.For example, on 8 February 1929, Britannia published an article titled “The Women of India”. It discussed child marriage, the caste system, and women’s restricted freedoms, ultimately framing Indian women as victims of regressive traditions. In particular, it claimed that “the customs of purdah ail” women and denied them education. The article ultimately frames British authority as essential to women’s emancipation, suggesting that only Britain could “inspire the peoples of that immense country by precept and example”.

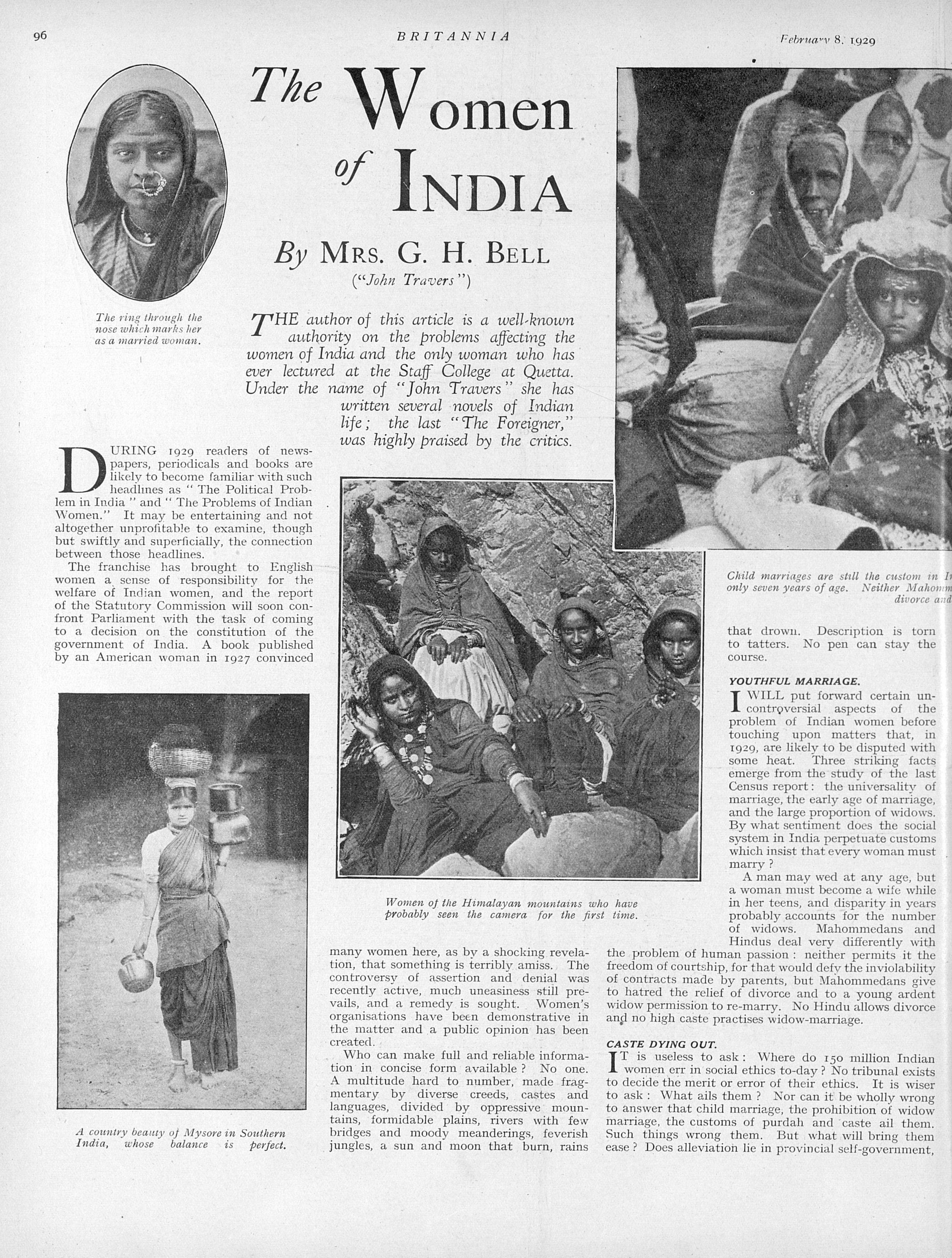

British Online Archives, The Illustrated London News, "The Impact of the Immigrants, 2 March 1968. Nearly forty years later, similar ideas resurfaced in The Illustrated London News in an article titled "The Impact of the Immigrants". Here, Indian and Pakistani women in Britain were described as seldom speaking English, “very fertile”, and resistant to British customs such as being examined by male doctors. Once again, South Asian women were depicted as the “other”—figures who strained national life and embodied cultural incompatibility.

British Online Archives, The Illustrated London News, "The Impact of the Immigrants, 2 March 1968. Nearly forty years later, similar ideas resurfaced in The Illustrated London News in an article titled "The Impact of the Immigrants". Here, Indian and Pakistani women in Britain were described as seldom speaking English, “very fertile”, and resistant to British customs such as being examined by male doctors. Once again, South Asian women were depicted as the “other”—figures who strained national life and embodied cultural incompatibility.

Taken together, these articles reveal how colonial and postcolonial print culture repeatedly stereotyped South Asian women as oppressed, different, and in need of Western intervention. Yet, scattered throughout these publications are women who defied such portrayals, women who campaigned for suffrage, pursued legal careers, and contributed to independence movements. By examining this coverage, this paper reconstructs a more complex history of South Asian women’s resilience, activism, and leadership.

Cornelia Sorabji: India’s First Female Lawyer

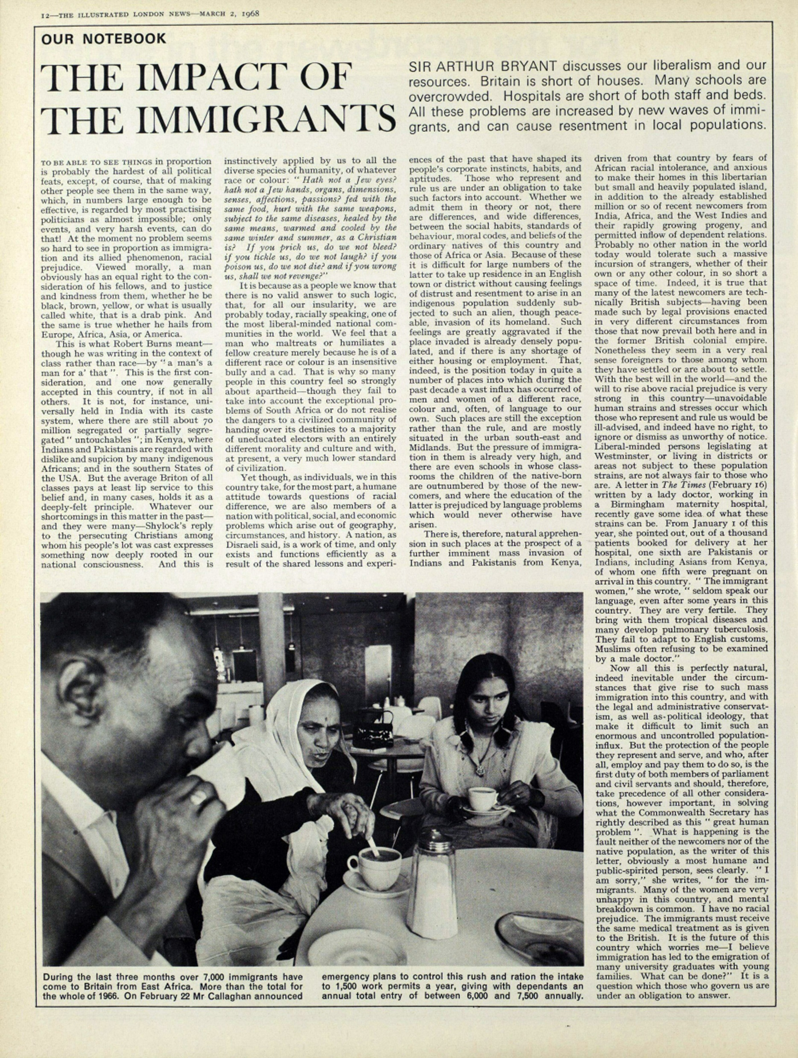

British Online Archives, The Sphere, "Three Notable Figures", 30 July 1904. One striking example of how South Asian women challenged British media stereotypes can be found in the coverage of Cornelia Sorabji. Born in 1866 in Western India, she broke multiple glass ceilings: she was the first woman to graduate from Bombay University, the first Indian woman to study law at Oxford, the first woman called to the English Bar in 1923, and the first female lawyer in India. Sorabji’s achievements directly contested the colonial narrative that Indian women were passive or uneducated.

British Online Archives, The Sphere, "Three Notable Figures", 30 July 1904. One striking example of how South Asian women challenged British media stereotypes can be found in the coverage of Cornelia Sorabji. Born in 1866 in Western India, she broke multiple glass ceilings: she was the first woman to graduate from Bombay University, the first Indian woman to study law at Oxford, the first woman called to the English Bar in 1923, and the first female lawyer in India. Sorabji’s achievements directly contested the colonial narrative that Indian women were passive or uneducated.

In 1889, she read Law at Sommerville College at the University of Oxford, becoming the first Indian woman to study at a British university. Despite barriers—such as being refused examination by male examiners—she persisted and in 1892 became not only the first woman, but the first South Asian woman in fact, to pass the Bachelor of Civil Laws (BCL) examinations at Oxford.

Returning to India in 1894, she dedicated her career to advocating for purdanasheen women, who were veiled and forbidden to speak with men. She worked tirelessly to give these women a legal voice. She earned her LLB from Bombay University in 1897 and petitioned the India Office for a female legal advisor for provincial courts by 1902. In 1904, she was appointed Lady Assistant to the Court of Wards of Bengal, ultimately representing over 600 women and children throughout her career. British Online Archives, The Graphic, "Our Portraits", 6 August 1904. On 2 January 1897, The Graphic published a section titled “Some January Reviews”. When touching on the topic of women studying at Oxford, they noted that “an Indian girl, Miss Cornelia Sorabji, is now practicing as a lawyer in Bombay”, further acknowledging that “she is the only B.C.L of her sex”. Cornelia appeared in The Graphic once again in August 1904, in its “Our Portraits” section, which reported that she had been appointed by the Bengal Government as legal advisor to the purdanasheen. Similarly, in July 1904, The Sphere named her one of the “Three Notable Figures of the Week”, alongside men, praising her efforts to provide “purdah ladies with qualified legal advice”.

British Online Archives, The Graphic, "Our Portraits", 6 August 1904. On 2 January 1897, The Graphic published a section titled “Some January Reviews”. When touching on the topic of women studying at Oxford, they noted that “an Indian girl, Miss Cornelia Sorabji, is now practicing as a lawyer in Bombay”, further acknowledging that “she is the only B.C.L of her sex”. Cornelia appeared in The Graphic once again in August 1904, in its “Our Portraits” section, which reported that she had been appointed by the Bengal Government as legal advisor to the purdanasheen. Similarly, in July 1904, The Sphere named her one of the “Three Notable Figures of the Week”, alongside men, praising her efforts to provide “purdah ladies with qualified legal advice”.

Cornelia was spotlighted again in The Illustrated London News in its "Books of the Day" supplement, which was published on 29 December 1934. After discussing her education, the piece explained how she had devoted herself to the cause of Indian women who “had no legal existence in India”. It noted that she rendered this service without fee, and that her work was recognised as socially important. Remarkably, as an Indian woman and a lawyer, Cornelia subverted the very structures that sought to marginalise Indian women.

These accounts are particularly noteworthy: for a woman, and a woman of colour, to be celebrated alongside men in publications aimed at British high society was exceptional. By highlighting her professional and intellectual achievements, these newspapers complicated the stereotype of Indian women as “backward and downtrodden”. Cornelia Sorabji’s career not only challenged institutional barriers in law but also redefined narratives in British print media, demonstrating that Indian women could assert agency, pursue education and legal rights, and shape their own and others stories.

Sarojini Naidu: The Nightingale of India Another figure who received attention in the British press was Sarojini Naidu, celebrated as both a poet and as an Indian independence activist. Born in 1879 to a Bengali family in Hyderabad, she showed academic brilliance from an early age. After passing her matriculation examination at twelve, she studied at King’s College London and later at Girton College, Cambridge, between 1895 and 1898.

Another figure who received attention in the British press was Sarojini Naidu, celebrated as both a poet and as an Indian independence activist. Born in 1879 to a Bengali family in Hyderabad, she showed academic brilliance from an early age. After passing her matriculation examination at twelve, she studied at King’s College London and later at Girton College, Cambridge, between 1895 and 1898.

During her time in England, she embraced suffragist ideas and engaged with notions of liberty, democracy, and nationalism through her interactions with both British and Indian intellectuals. This experience awakened her political consciousness and laid the groundwork for her future activism.

On returning to India, she became deeply involved in the independence movement led by the Indian National Congress. She worked closely with Gandhi and participated in non-violent protests and became one of the first women to play a leading role in the struggle for self-rule. In 1925, she was elected the first female president of the Indian National Congress, and in 1931 she accompanied Gandhi to London for the Round Table Conference, where she directly addressed British audiences on Indian self-rule and women’s rights.

Alongside her political work, Naidu shaped India’s literary and cultural life. She became one of the first Indian women to gain international fame as a writer, with her English-language poetry earning her the title “Nightingale of India”.

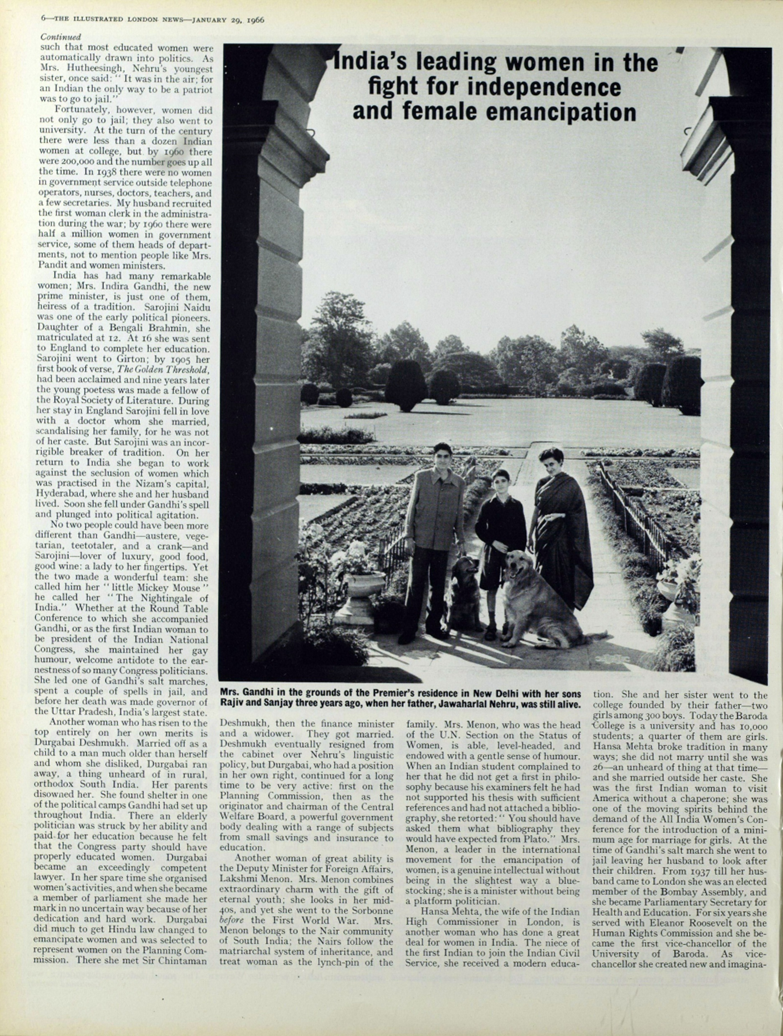

British Online Archives, The Illustrated London News, "India in Ferment: Notable Incidents and Prominent Personalities", 17 May 1930.British newspapers often highlighted Naidu’s eloquence and charisma. On 29 January 1966, The Illustrated London News cited her as one of the early political pioneers of Indian independence when discussing remarkable Indian women. In the decade leading up to independence, she was frequently pictured alongside nationalist leaders—often the only woman included in such coverage.

British Online Archives, The Illustrated London News, "India in Ferment: Notable Incidents and Prominent Personalities", 17 May 1930.British newspapers often highlighted Naidu’s eloquence and charisma. On 29 January 1966, The Illustrated London News cited her as one of the early political pioneers of Indian independence when discussing remarkable Indian women. In the decade leading up to independence, she was frequently pictured alongside nationalist leaders—often the only woman included in such coverage.

British Online Archives, The Sphere, "India and the New Constitution", 10 April 1937. Articles also emphasised her resilience and devotion to the independence movement. For instance, The Sphere article “India and the New Constitution”, which appeared in 1937, repeatedly pictured her, underscoring her importance within Indian nationalist politics. Her achievements were regularly praised, with publications describing her as the “only woman who has been President of the Indian Congress”, a “distinguished Indian poetess and political leader”, and a feminist.

British Online Archives, The Sphere, "India and the New Constitution", 10 April 1937. Articles also emphasised her resilience and devotion to the independence movement. For instance, The Sphere article “India and the New Constitution”, which appeared in 1937, repeatedly pictured her, underscoring her importance within Indian nationalist politics. Her achievements were regularly praised, with publications describing her as the “only woman who has been President of the Indian Congress”, a “distinguished Indian poetess and political leader”, and a feminist. British Online Archives, Britannia and Eve, "Woman of the East", July 1938.Naidu’s literary reputation further shaped her image in Britain. An article in The Graphic in May 1920 celebrated her international reach, declaring that “Sarojini Naidu has sent India’s fame flashing over both hemispheres”. Similarly, a Britannia and Eve article described her as a “fiery woman political leader of India”. Naidu herself also challenged stereotypes about Indian women. In a 1928 speech in the United States, she told her audience:

British Online Archives, Britannia and Eve, "Woman of the East", July 1938.Naidu’s literary reputation further shaped her image in Britain. An article in The Graphic in May 1920 celebrated her international reach, declaring that “Sarojini Naidu has sent India’s fame flashing over both hemispheres”. Similarly, a Britannia and Eve article described her as a “fiery woman political leader of India”. Naidu herself also challenged stereotypes about Indian women. In a 1928 speech in the United States, she told her audience:

It might surprise you that a country which you are taught to regard as conservative should have chosen a woman to be its representative and ambassador, but if you read the whole history of Indian Civilization you will realise that women have been the very pivot of its culture, of all its inspirations, and of all the embassies of peace that have gone abroad for many centuries to the uttermost parts of the world.

The emphasis on the word “taught” is crucial. Naidu directly pointed to the way in which colonial narratives shaped Western assumptions about Indian women. By reminding her audience that historically, women had been central to Indian civilization, she both corrected misconceptions and expressed cultural pride on the global stage.

Taken together, her speeches, career, and representations in the British press complicate the dominant colonial narrative of South Asian women as voiceless and oppressed. Instead, Naidu appeared as an accomplished poet, a gifted orator, and a determined political leader. Her prominence in British periodicals demonstrates that South Asian women were powerful agents of change who could inspire both Indian and international audiences.

Hansa Mehta: Rewriting Women’s Rights on the World Stage

British Online Archives, The Illustrated London News, 29 January 1966.

British Online Archives, The Illustrated London News, 29 January 1966.Another fascinating woman that spoke up for South Asian women’s rights was Hansa Mehta. Born in 1897, this Gujarati woman was a prominent educator, reformer, and politician who played a crucial role in shaping women’s rights internationally. After graduating with honours from Baroda College in India, in 1919 she studied Journalism and Sociology at the London School of Economics. It was there that she began her lifelong mission of fighting for Indian women’s equality at a time when most were still confined to the home.

She later became president of the All India Women’s Conference, where she proposed and drafted the Indian Women’s Charter of Rights and Duties. This charter demanded equal rights to education, equal pay, equal property distribution, and equality in marriage and divorce laws. Mehta was also one of only fifteen women in India’s Constituent Assembly, where she continued her fierce advocacy of equal rights for women and was instrumental in drafting the Constitution of India.

Her activism extended to the global stage. From 1947 to 1952, she served as India’s delegate to the United Nations Commission on Human Rights. There, working alongside Eleanor Roosevelt, she fought the case for a gender-neutral phrasing of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights. The initial wording of Article 1 was “All men are born free and equal in dignity and rights”. She was instrumental in altering the wording from “all men” to “all human beings”. Her career demonstrates how South Asian women not only resisted oppression within colonial and national contexts but also reshaped global understandings of equality and freedom. British Online Archives, The Illustrated London News, 29 January 1966.On 29 January 1966, The Illustrated London News described Mehta as “another woman who has done a great deal for women in India”, praising her leadership in the All India Women’s Conference and her role in introducing a minimum age for marriage for girls.

British Online Archives, The Illustrated London News, 29 January 1966.On 29 January 1966, The Illustrated London News described Mehta as “another woman who has done a great deal for women in India”, praising her leadership in the All India Women’s Conference and her role in introducing a minimum age for marriage for girls.

The article concluded with the striking statement that:

The name Hansa Mehta rings the same bell in India that the names Pankhurst and Nightingale ring in England.

This comment speaks volumes of Hansa’s impact, similar to Pankhurst’s activism, Hansa directly countered the stereotype of Indian women as passive victims. The very fact that a South Asian woman was compared to Pankhurst and Nightingale underscores how profoundly she unsettled colonial stereotypes of Indian women as passive or voiceless. Hansa’s career demonstrates that South Asian women were not only participants but leaders in rewriting the meaning of freedom and justice in the twentieth century.

Conclusion

The representations of Cornelia Sorabji, Sarojini Naidu, and Hansa Mehta reveal the contradictions within British print media’s portrayals of South Asian women. This paper has shown that South Asian women were not merely subjects of imperial discourse but active participants who challenged, negotiated, and redefined it. Sorabji’s legacy in the field of law, Naidu’s prominent role in the Indian independence movement, and Mehta’s role in altering the Universal Declaration of Human Rights all demonstrate that South Asian women did not “seldom speak English”, nor did they require Britain to model freedom for them or free them of the shackles of a supposedly backward culture. They were fully capable of defining, demanding, and enacting emancipation on their own terms. By surveying their presence within British print media, this paper has reconstructed a more complex history of South Asian women’s resilience, activism, and leadership.

Their activism also underscores the ongoing need to reconsider how history is taught and to decolonize the curriculum. These histories remain largely absent from mainstream education. While figures like Emmeline Pankhurst or Florence Nightingale are routinely celebrated as icons of women’s history in Britain, women like Sorabji, Naidu, and Mehta, whose legacies show that South Asian women were central to global struggles for equality, are rarely acknowledged. It is vital that the contributions of influential people of colour are more widely recognised, both to foster a more inclusive understanding of history and to allow young people of colour to see themselves reflected in the past. Whether South Asian, African, or Caribbean, these figures demonstrate that individuals from diverse backgrounds have long shaped the world we live in today.